It’s been almost a year since I posted. A family crisis and intensive work have filled my time, but things are easing and I am intending to publish every two months going forward. In the last year I’ve been adapting to ArcGIS Pro, so expect some posts and videos about that in future. I’ve also been working on the Egypt Exploration Society’s Delta Survey Online web-map, which you can go and interact with at https://www.ees.ac.uk/our-cause/research/delta-survey.html. Just follow the last tab to the ‘Delta Survey Online’ (scroll down to the bottom of the page if you are on a handheld device) and view the data in the embed, or click through to the ArcGIS Online map to explore, analyse and export.

The Asyut Region Project

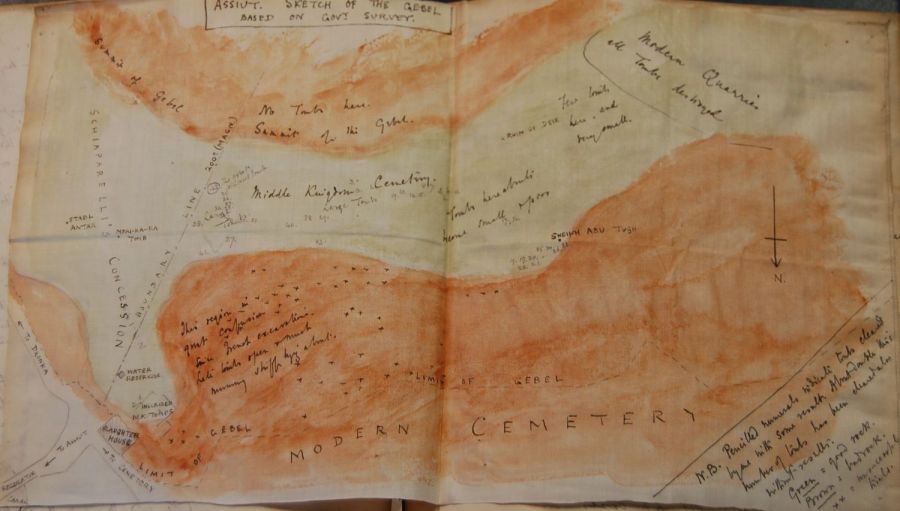

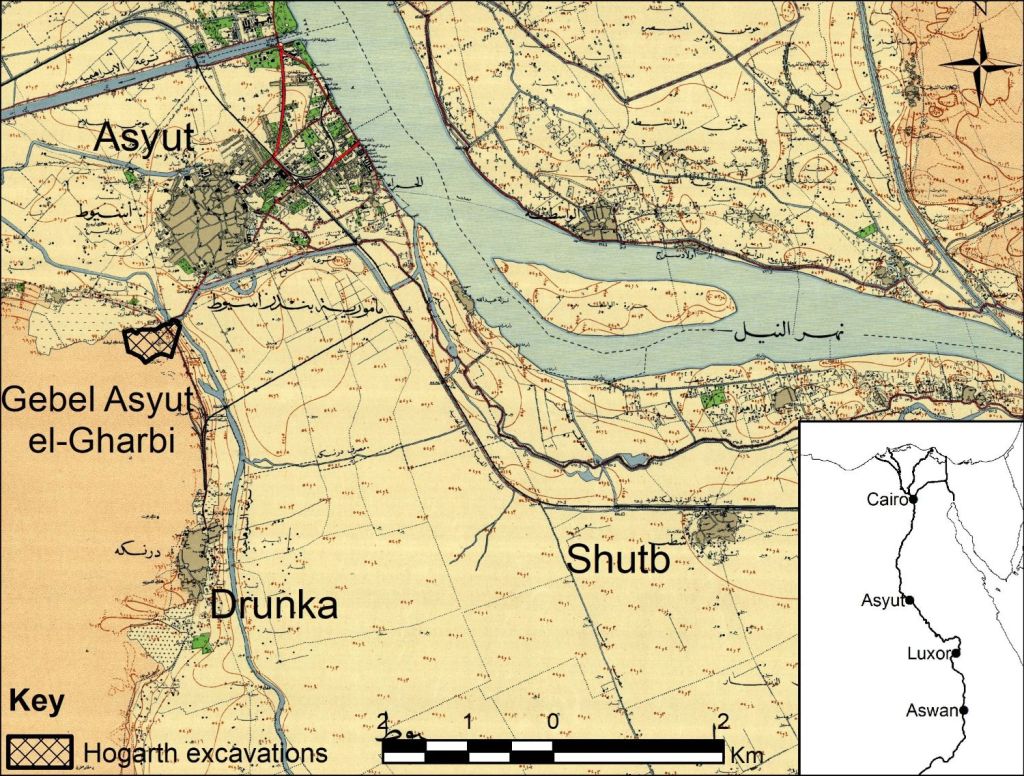

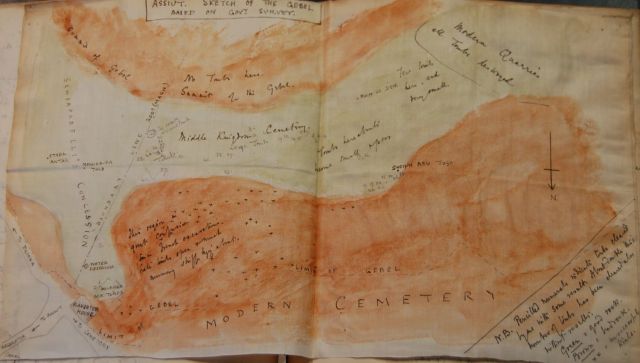

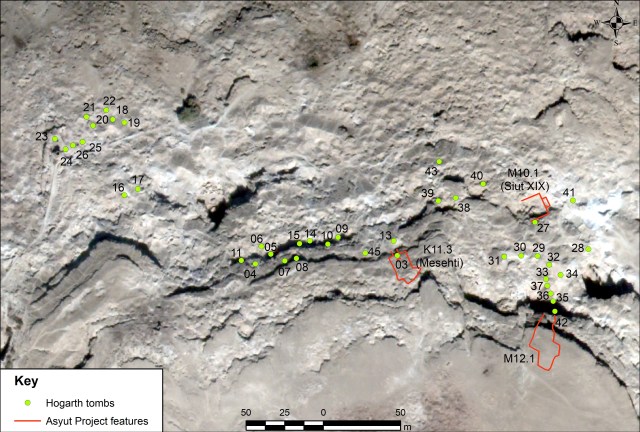

In 2017-19 I worked on the Asyut Region Project, looking at the archive of David George Hogarth’s excavations in 1906-7 at Asyut. I continued this research independtly after the end of the project and a paper from this work has recently been published. My 2024 article in Interdisciplinary Egyptology, ‘Resurrecting the Archive: Revitalising records of Hogarth’s excavations in the Gebel Asyut el-Gharbi necropolis, Egypt 1906–1907’, proposes approximate locations for the tombs Hogarth excavated on the Gebel Asyut el-Gharbi in 1906-7, based on his sketch-map, the descriptions in his Notebook and Diary and some judicious satellite-imagery-based detective work (Pethen 2024). You can read all about it at https://doi.org/10.25365/integ.2025.v4.1.

During the course of this research and while working on my previous article on the Hogarth’s pottery corpus (Pethen 2021), I noted that it was possible to track Hogarth’s movement across the Gebel Asyut el-Gharbi from the combination of his Diary and Notebook entries and the approximate locations of the tombs he excavated. It was not possible to visualise the progress of the excavation in the published articles, but it can be visualised in an ArcGIS Story Map.

Dating Hogarth’s tombs by discovery or excavation date

Before creating a Story Map showing how Hogarth moved across the Gebel between December 1906 and February 1907, it was necessary to cross-reference the records in Hogarth’s Notebook and Diary to determine when he first found each of the tombs in the sketch-map. I used the earliest dated reference to a tomb in either document. Given the somewhat variable nature of Hogarth’s recording (for more details of which see Pethen 2021; 2024), this means that the date associated with the tombs is sometimes the date that Hogath first noted the tomb, and sometimes the first day of the excavation. The table below shows the dates first associated with the tomb, details of how the tomb that date was determined, together with the area where the tomb is located.

| Number | Date | Details | Area |

| Tomb 1 | 17 December 1906 | Tomb 1 is only recorded in Hogarth’s Notebook (page 2), because the Diary does not start until Jan 1 1907. | Salakhana |

| Tomb 2 | 19 December 1906 | Tomb 2 is only recorded in Hogarth’s Notebook (page 8), because the Diary does not start until Jan 1 1907. | Salakhana |

| Tomb 3 | 19 December 1906 | Tomb 3 is only recorded in Hogarth’s Notebook (page 12), because the Diary does not start until Jan 1 1907. | High Terrace |

| Tomb 4 | 21 December 1906 | Tomb 4 is only recorded in Hogarth’s Notebook (page 14), because the Diary does not start until Jan 1 1907. | High Terrace |

| Tomb 5 | 28 December 1906 | Tomb 5 is only recorded in Hogarth’s Notebook (page 18), because the Diary does not start until Jan 1 1907. | High Terrace |

| Tomb 6 | 28 December 1906 | Tomb 6 is only recorded in Hogarth’s Notebook (page 20), because the Diary does not start until Jan 1 1907. | High Terrace |

| Tomb 7 | 29 December 1906 | Tomb 7 is only recorded in Hogarth’s Notebook (page 22), because the Diary does not start until Jan 1 1907. | High Terrace |

| Tomb 8 | 31 December 1906 | Tomb 8 is only recorded in Hogarth’s Notebook (page 24), because the Diary does not start until Jan 1 1907. | High Terrace |

| Tomb 9 | 01 January 1907 | Tomb 9 is first recorded in Hogarth’s Notebook (page 28) and in his Diary (page 1) on the 1st January 1907. | High Terrace |

| Tomb 10 | 01 January 1907 | Hogarth’s Diary (page 1) suggests he was aware of Tomb 10 by the 1st January through a robber hole, although the first date associated with this tomb in his Notebook (page 30) is the 3rd January. | High Terrace |

| Tomb 11 | 04 January 1907 | Hogarth’s Diary (page 3) entry suggests he first saw Tomb 11 on the 3rd January, but the tomb he describes might be another. The first date in his Notebook (page 34) related to the 4th January. | High Terrace |

| Tomb 13 | 04 January 1907 | The earliest mention of Tomb 13 is in Hogarth’s Notebook (page 40) dated 4th January. | High Terrace |

| Tomb 14 | 05 January 1907 | Hogarth’s Notebook (page 42) records the first mention of Tomb 14 dated to the 5th January. | High Terrace |

| Tomb 15 | 07 January 1907 | Hogarth’s Diary (page 7) and Notebook (page 44) agree that the first record of Tomb 15 was the 7th January 1907. | High Terrace |

| Tomb 16 | 12 January 1907 | Hogarth’s Notebook (page 46) records the first date associated with Tomb 16 as the 12th January. It may be one of the tombs ‘below Abu tug’ referred to in the Diary (page 12) entry of 12th January. | Abu Tugh |

| Tomb 17 | 12 January 1907 | Hogarth’s Notebook (page 50) records the first date associated with Tomb 17 as the 12th January. This may be one of the tombs ‘below Abu tug’ referred to in the Diary entry of 12th January, page 12. | Abu Tugh |

| Tomb 18 | 12 January 1907 | Hogarth’s Notebook (page 54) records the first date associated with Tomb 18 as the 12th January. This may be one of the tombs ‘below Abu tug’ referred to in the Diary entry of 12th January, page 12. It is first mentioned by number in the Diary (page 21) entry of the 14th January. | Abu Tugh |

| Tomb 19 | 14 January 1907 | Hogarth’s Notebook (page 56) records the first date associated with Tomb 19 as the 14th January. This may be one of the tombs ‘below Abu tug’ referred to in the Diary (page 12) entry of 12th January. It is first mentioned by number in the Diary (page 14) entry of the 14th January. | Abu Tugh |

| Tomb 27 | 14 January 1907 | Hogarth’s Notebook (page 72) dates excavation of Tomb 27 from the 14th. It is probably the ‘large roofless tomb near our dwelling place’ mentioned in his Diary (page 14) entry of 14th January. Tomb 27 is first mentioned by number in the Diary (page 21) on the 21st January. | 27 Group |

| Tomb 20 | 15 January 1907 | Hogarth’s Notebook (page 58) first records activity at Tomb 20 on the 15th January. This may be the tomb, near Tombs 18 and 19, that was located ‘before night’ on the 14th January in the Diary (page 14) entry of that date, but this is uncertain. | Abu Tugh |

| Tomb 21 | 15 January 1907 | Hogarth’s Notebook (page 60) and Diary (page 15) agree in the first mention of Tomb 21 on the 15th January. | Abu Tugh |

| Tomb 22 | 16 January 1907 | Hogarth’s Notebook (page 62) and Diary (page 16) agree that Tomb 22 was first investigated on the 16th January. | Abu Tugh |

| Tomb 23 | 16 January 1907 | Hogarth’s Notebook (page 64) and Diary (page 16) agree that Tomb 23 was found late on the 16th but excavation began on the 17th January. | Abu Tugh |

| Tomb 24 | 17 January 1907 | Hogarth’s Notebook (page 66) and Diary (page 17) agree that Tomb 24 was found on the 17th January. | Abu Tugh |

| Tomb 25 | 17 January 1907 | Hogarth’s Notebook (page 68) and Diary (page 17) agree that Tomb 25 was found on the 17th January. | Abu Tugh |

| Tomb 26 | 17 January 1907 | Hogarth’s Notebook (page 70) and Diary (page 17) agree that Tomb 26 was found on the 17th January. | Abu Tugh |

| Tomb 42 | 22 January 1907 | Hogarth’s Notebook (page 104) and Diary (page 22) agree that Tomb 42 was discovered on the 22nd January 1907. Although the Diary (page 42) does not mention the tomb by number until the 11th February, the description of clearing the dromos of a large tomb on the 22nd January is an unmistakeable reference to tomb 42. | 42 Group |

| Tomb 28 | 23 January 1907 | Hogarth’s Notebook (page 78) provides the earliest date for Tomb 28’s discovery as the 23rd January 1907. The Diary (page 25) only mentions this tomb on the 25th January. | Tomb 28 |

| Tomb 29 | 26 January 1907 | Hogarth’s Notebook (page 80) notes that Tomb 29 was first discovered on the 26th January, although the comment is dated ‘Jan 27’. The Diary (page 27) first refers to tomb 29 on the 27th January. As discussed by Pethen (2024,17) this tomb was almost certainly one of ‘five tomb doors’ noted by Hogarth in his Diary (page 26) entry of the 26th January. | 29 Group |

| Tomb 30 | 26 January 1907 | The first date in Hogarth’s Notebook (page 82) for Tomb 30 is the 27th January. The only Diary (page 28) entry referring indirectly to Tomb 30 is a reference to the ‘XXIX group’ from the 28th January. As discussed by Pethen (2024, 17) this tomb was almost certainly one of ‘five tomb doors’ noted by Hogarth in his Diary (page 26) entry of the 26th January. | 29 Group |

| Tomb 31 | 26 January 1907 | The first date in Hogarth’s Notebook (page 84) under Tomb 31 is dated 27th January. The only Diary (page 28) entry referring indirectly to Tomb 31 is a reference to the ‘XXIX group’ from the 28th January. As discussed by Pethen (2024,17) this tomb was almost certainly one of ‘five tomb doors’ noted by Hogarth in his Diary (page 26) entry of the 26th January. | 29 Group |

| Tomb 34 | 28 January 1907 | Hogarth’s Notebook (page 88) first records a date of the 30th January under Tomb 34 but states that Hogarth had been ‘trying to get into this tomb for 2 days’ implying it was first found on the 28th January. His Diary (page 28) names a tomb whose description matches this one as discussed in Pethen (2024, 17). | 29 Group |

| Tomb 32 | 29 January 1907 | Hogarth’s Notebook (page 84) and Diary (page 29) agree the first activity relating to Tomb 32 took place on the 29th January. | 29 Group |

| Tomb 33 | 29 January 1907 | Hogarth’s Notebook (page 86) records the first activity relating to Tomb 33 on the 29th January. His Diary (page 31) mentions Tomb 33 on the 31st January, but the description indicates this is probably and error and he means tomb 34. | 29 Group |

| Tomb 35 | 31 January 1907 | Hogarth’s Notebook (page 90) records under Tomb 35 on the 1st February, ‘entered this tomb yesterday’, indicating it was entered on the 31st January. The Diary (page 32) first mentions this tomb in the entry for the 1st February, but the entry (page 31) for the 31st January mentions ‘two large tombs with quarried fronts’ one of which is identifiable as 35 (Pethen 2024, 17). | 42 Group |

| Tomb 36 | 31 January 1907 | Hogarth’s Notebook (page 92) does not give a date for Tomb 36, but confirms it was in same row as tomb 35. His Diary (page 31) indicates it was found on the 31st January together with tomb 35 as discussed in Pethen (2024, 17). | 42 Group |

| Tomb 37 | 01 February 1907 | Hogarth’s Notebook (page 94) only indicates that Tomb 37 was finished on the 1st February. The first description of this tomb is in his Diary (page 32) entry for the 1st February, where the tomb is identifiable by its relation with tomb 35 (Pethen 2024, 17). | 42 Group |

| Tomb 38 | 02 February 1907 | Hogarth’s Notebook (page 96) and Diary (page 33) agree that the first date associated with Tomb 38 was the 2nd February. | 27 Group |

| Tomb 39 | 02 February 1907 | The Diary (page 33) entry of 2nd February describes Tomb 39 but incorrectly refers to it as Tomb 37. When the misidentification is corrected Notebook (page 98) and Diary agree. | 27 Group |

| Tomb 40 | 02 February 1907 | Hogarth’s Notebook (page 100) entry for this Tomb 40 on the 5th February states, ‘Have been going down the shaft for 3 days’ indicating the tomb was opened at latest on the 2nd February. The first mention of this tomb in the Diary (page 33) is on the 5th February. | 27 Group |

| Tomb 41 | 08 February 1907 | Hogarth’s Notebook (page 102) and Diary (page 39) agree that the first date associated with Tomb 41 was the 8th February. | 27 Group |

| Tomb 43 | 09 February 1907 | Hogarth’s Notebook (page 106) and Diary (page 40) agree that the first date associated with Tomb 43 was the 9th February. | 27 Group |

| Tomb 45 | 12 February 1907 | Hogarth’s Diary (page 43) describes the discoveries from Tomb 45 under the name ‘XLI’V (44) owing to the confusion in Hogarth’s records as per Pethen (2024, 14). Allowing for this the Notebook (page 108) and Diary agree that the date associated with this tomb is the 12th February. | Return to the High Terrace |

Another thing to bear in mind is that Hogarth often left a team working at a tomb while he moved on to new places for investigation. Tomb 42 in particular was a large tomb, with an approach (which Hogarth referred to as a dromos but is best visualised as being like the ’causeways’ of the tombs at Qubbet el-Hawa) Hogarth’s Tomb 41 has since been identified as Asyut Project tomb M12.1 (Pethen 2024, 18, following Kahl et al., 2006: 246; Zitman 2010a: 43). Hogarth began excavating this tomb on the 22 January and continued until the 16th of February (Hogarth Notebook 1907, 104-5), all while other teams worked on Tombs 29-45. Work on Tomb 27, which might be the same tomb as M10.1/Siut XIX (Pethen 2024, 18 following Kahl et al., 2007: 84; Palanque 1903: 119–121; Zitman 2010a: 40–42; 2010b: 6, map 3) began on the 14th January and continued until 1st February (Hogarth Notebook 1907, 72-74) all while teams also investigated Tombs 20-26 and 28-36. There are also areas Hogarth had investigated that he never wrote up because he didn’t find anything he considered worth recording. All of this means that while we can track Hogarth’s focus, there were many excavations ongoing at various different locations in the necropolis at any one time. Nevetheless, it was an interesting experiment and I think it demonstrates how Hogarth’s focus shifted as his excavation developed.

Following Hogarth

Hogarth’s progress across the Gebel Asyut el-Gharbi appears relatively straightforward. He began at the north-east foot of the Gebel investigating the so-called Salakhana tomb (DuQuesne 2009) area in mid-December 1906, recording Tomb 1 and 2. He the rapidly moved up to the top of the Gebel around the 19th December, to investigate the area around the tomb of Mesehti, which he called ‘Farag’s Tomb’. This was the tomb which produced the famous models late in 19th-century, and was later relocated by the Asyut Project who numbered it K11.3 (Kahl et al., 2018: 145–151; Zitman 2010a: 17). Hogarth called it ‘Tomb 3’. Hogarth continued on the two high north-facing terraces along from and below Tomb 3 until the middle of January, only moving north-west and down the slope towards the memorial to the Sheikh Abu Tugh on the 12th January 1907 when he began Tomb 16 and 17. His focus remained on the area around Sheikh Abu Tugh’s memorial until the 23rd January, but his team began to excavate Tomb 27 in the lower slopes of the eastern part of his concession on or around the 14th January. Thereafter his focus slowly moved towards the eastern end of his concession. He began clearing the dromos, or carved approach, to Tomb 42 (now known as Asyut Project tomb M12.1) on the 22nd January and Tomb 28 on the 23rd January. He located what he called ‘The 29 Group’ (including Tombs 29, 30, 31) on the 26th Janaury and continued to work in the same area, finding tombs 32-34 nearby in the days following. At the very end of January he moved up to the top of the terrace at the eastern end of his concession, finding Tombs 35-37 close to Tomb 42. In early February his focus shifted again, to the lower slopes around Tomb 27, where he had finished work on the 1st February. Tombs 38-40 (all found on the 2nd February) and 43 (found on the 9th February) were all located west of Tomb 27 at roughly the same level, while Tomb 41 (found on the 8th February) was east of Tomb 27, as apparently was Tomb 44, although it was missed off Hogarth’s sketch map (Pethen 2024, 14). The last tomb recorded on the sketch map was Tomb 45, found on the 12th February back up on the high terrace to the west of Tomb 3 (Mesehti), the day before Hogarth posted his sketch map to London. He found further tombs before he finished at Asyut, but their location was not included on the sketch map and is therefore beyond the scope of this post.

Modelling Hogarth’s movements in ArcGIS Story Maps

ArcGIS Story Maps allow you to create a series of points with images and descriptions which can visitors can either explore or be guided through on the geographical journey. They require no GIS skills on the part of the visitors and are therefore an ideal way to disseminate certain types of GIS information. A Story Map of Hogarth’s movements across the Gebel Asyut el-Gharbi according to the dates of the tombs marked on his sketch map seemed a suitable complement to my paper on locating Hogarth’s tombs. For my Story Map please follow the link to https://arcg.is/09H4GP0 where you can view the two map-tours and my thoughts about how they work.

The Story Map template operates very similarly to a blog, in fact it reminded me very much of creating posts here because it works with blocks just like wordpress. Using the blocks is very straightforward and will seem familiar if you have used a blog or similar webpage builder before. But the point of Story Maps, is the ‘map’ part and there it becomes a little more complex. There are two basic methods of entering the points in your Story Map, you can simply drop points on a basemap in the Story Map builder, adding your own description and images as you go. This is how I built the Capitals of Lower Egypt Story Map for the EES Study Day on important Lower Egyptian sites. It works very well if the locations on your Story Map are easily identifiable in the standard ArcGIS basemaps or satellite imagery.

Alternatively you can upload your Story Map points as a Feature Service, essentially a spreadsheet that ArcGIS Online converts to a vector layer. This is the method I used, since I already had the approximate tomb positions based on my previous research (left, after Pethen 2024, fig. 8). It sounds super-simple, particularly if you’ve done any GIS before and you’re familiar with attribute tables as .dbf files and using .csv to enter data. That said, you can’t simply export an attribute table, convert to .csv and upload to ArcGIS Online. You will need to edit the file so it conforms to the fields that the Story Map builder is expecting. And here we can see that Story Maps truly are a GIS product because like GIS in general they are ‘picky eaters’, when it comes to ingesting and doing things with data. Essentially the Story Map builder is expecting a ‘Place Title’ field, Latitude and Longitude fields to give the coordinates of your points and a ‘Description’ field. There is also an option to include a button link (to a website or similar) and Story Maps are created with the anticipation that you will include images of each point, so you can include an image attribute or link to the image in your spreadsheet, but its also possible to add that later. You can have as many fields as you want in your Feature Service spreadsheet, but the Story Map will ONLY show the ‘Name’ and ‘Description’ fields and the image. You can pick which fields you want to use for ‘Name’ and ‘Description’ but you can’t include multiple fields like in an webmap popup. I used a version of the table shown above, but I included the date first associated with the tomb in the ‘Details’ column, which I also renamed ‘Description’. With the addition of Latitude and Longitude fields (which I excluded from the table above) I then had all the details I needed for the Story Map, but I would have preferred to include the ‘Date’ column separately as I could do with a web popup.

The guided map displays your points in the order they are listed in your Feature Service, so you need to make sure your spreadsheet has its rows in the correct order, before you upload it. You should also make sure all the information you want displayed is collated in the field you will designate ‘Description’ because as mentioned above, Story Map embeds only display Title and Description text fields. You may also want to organise your categories if you intend to categorise your data in the Story Map, remembering as of 2025 there is an 8 category limit.

Overall I was quite impressed with the Story Map, although I would love to have increased options in terms of fields, and more functionality to edit the order and details within the app. I felt both the guided tour and the categorised tour offered some interesting options for this type of chronological/geographical data. Let me know in the comments which one you think worked best, and if ESRI ever read this, what functionality you’d like added to the Story Maps.

References and Acknowlegdements

The first part of this research was undertaken while I was Asyut Project Curator at the British Museum in 2017-2018 and 2018-2019 during the Asyut Region Project, under the directorship of Dr Ilona Regulski. The Asyut Region Project was funded by an Institutional Links grant, ID 274662441, under the Newton-Mosharafa Fund partnership. The grant is funded by the UK Department of Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) and delivered by the British Council.

I have used ‘Hogarth’s excavations/movements etc’ here for clarity and because as director, he chose where to excavate and therefore was directly responsible for the movement across the Gebel, with which this post is primarily concerned. Nevertheless, it should be remembered that he had a large number of workers, most, if not all, of whom were Egyptian and included a number of local workers plus at least one Reis or foreman, and potentially some other trained Qufti archaeologists.

ArcGIS® software by Esri. ArcGIS® and ArcMap™ are the intellectual property of Esri and are used herein under license. Copyright © Esri. All rights reserved. For more information about Esri® software, please visit http://www.esri.com .

The Hogarth Archive

The dating of the tombs and other evidence presented in this post comes from Hogarth’s Notebook and Diary, while the location of the tombs is derived from his Sketch Map, with evidence from the written archive and satellite remote sensing as detailed in Pethen (2025). All these documents are in the archives at the British Museum. The references for the Hogarth documents are as follows:

Hogarth, D. G. (1907a.) Assiut Tombs 1906-7: Notebook. Unpublished field notes. British Museum AES Archive. 313 1.5.3.

Hogarth, D. G. (1907d.) Assiut Sketch of the Gebel. Unpublished map of Hogarth’s research. British Museum Dept of Egyptian and Assyrian Antiquities, Correspondence 1907 A-K, 321.

Hogarth, D. G. (1907e.) Diary. Unpublished diary from the Asyut excavations 1907. British Museum AES Archive. 313 1.5.3.

Academic books and papers

DuQuesne, T. (2009.) The Salakhana Trove: Votive Stelae and Other Objects from Asyut. Darengo Publications.

Kahl, J., El-Hamrawi, M., Verhoeven, U., and El-Nasir Yasin, A., (2018.) The Asyut Project: Thirteenth Season of Fieldwork (2017). Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur 47: 137–148.

Pethen, H. (2021) A New Year Pottery Corpus: investigating early 20th century excavation methods through the Hogarth excavation archive at the British Museum. Bulletin de la Céramique Égyptienne. 229–246.

Pethen, H. 2024, ‘Resurrecting the Archive: Revitalising records of Hogarth’s excavations in the Gebel Asyut el-Gharbi necropolis, Egypt 1906–1907’, Interdisciplinary Egyptology 4/1: 1-27 https://doi.org/10.25365/integ.2025.v4.1 .

Zitman, M. (2010a.) The Necropolis of Assiut: A case study of local Egyptian funerary culture from the Old Kingdom to the end of the Middle Kingdom. Text. Volume 1. OLA 180. Peeters.

Zitman, M. (2010b.) The Necropolis of Assiut: A case study of local Egyptian funerary culture from the Old Kingdom to the end of the Middle Kingdom. Maps, Plans of Tombs, Illustrations, Tables, Lists. Volume 2. OLA 180. Peeters.