In my previous post, I discussed a Telegraph article, published on 17 June 2024 which criticised the Pitt Rivers Museum for ‘hiding’ objects that women were not supposed to see. You can find an archived version of the original Telegraph article here. While Madeline Odent (@oldenoughtosay) on Twitter and the Pitt Rivers Museum (in this article) rebutted most of the claims made by the Telegraph, it would not have been nearly as effective without certain gross misunderstandings of what museums are and how they work. I previously wrote here about how the redisplay of certain Wellcome Museum galleries was subject to similar misunderstandings in 2022, but it seems these misunderstandings continue. They may even be more intense in Wunderkammer-style museum, like the Pitt Rivers, which is as Madeline Odent puts it, ‘somewhat unusual among modern museums in that it has largely kept to its Victorian roots of ‘cram as many artefacts as possible into each display case’.

What is a museum?

Museums, especially archaeological museums, often combine the function of object warehouse, educational institute, and art gallery. As I described in my post about the Wellcome Museum, the latter two functions are what we experience when we visit the museum galleries, or an exhibition of objects from the museum (either in the same building or elsewhere). The publicly open galleries and exhibitions do not constitute the whole Museum. They are simply the part of the museum that is prepared for public visitation with carefully curated objects and relevant signage. This is more obvious when we visit a museum with a limited number of artefacts carefully displayed, but even then I suspect many people assume that that which is on display constitutes the entire museum. In this respect, the Wunderkammer-style of the Pitt Rivers, is a disadvantage, because the very large number of items on display itself suggests that the entire collection is visible. In fact, the visible artefacts in publicly open galleries and exhibition spaces only ever constitute a relatively small proportion of any museum’s holdings! The Igbo mask, the focus of the Telegraph’s article, has not been ‘hidden’. It was never on display, along with much of the rest of the collection!

The Collection

The majority (exact proportions vary) of any museum’s holdings are held in storage. Together the objects in storage and those on display are described as the museum’s collection. Some of these objects are not on display because they are fragile or would be at risk in some way. Some are sufficiently similar to objects on display that including them would clutter display cases without adding further interest or value. Others are simply extremely boring to any but dedicated specialists. The holdings of archaeological museums, especially those which have received objects from archaeological excavations, often include large numbers of pottery sherds, flints, and animal bones. These are retained, together with relevant archival records about their archaeological context, so that specialists can draw further conclusions about the sites which produced them, identify similarities with material from elsewhere, and check the conclusions of the original excavators. They are incredibly useful objects but would make for extremely dull displays.

The Catalogue

While most of a museum collection is physically inaccessible to the public, many museums have online catalogues which include records of all their objects, many including photographs. The online catalogue, with its details and photographs, is publically accessible and allows both the public and researchers to browse the entire collection.

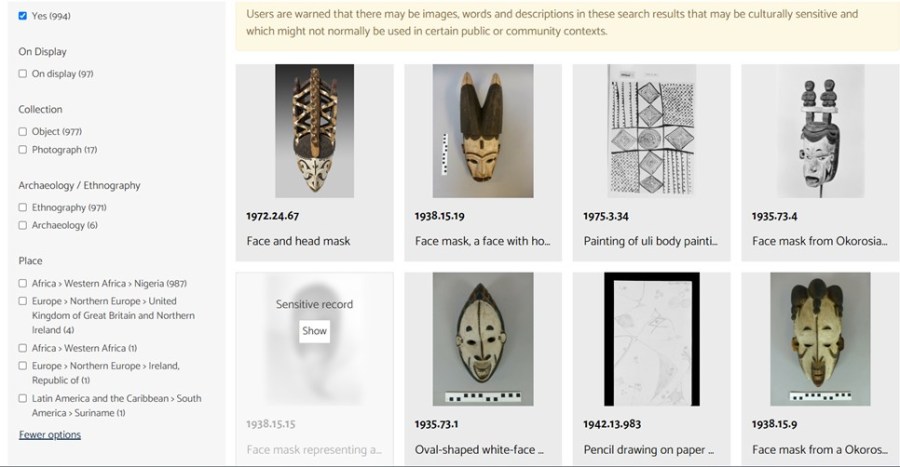

The amount of information available in an online catalogue varies hugely, and since these records are often digitised versions of old card catalogues or accession ledgers, they may include outdated terms and definitions. This is why when you click on ‘Collections online’ on the Pitt Rivers website, you’ll see a pop-up (image above) warning you that ‘some records will also document research about peoples and cultures using scientific research models and language that are outdated and may be offensive.’ The record you may be reading might not have been changed since the object was entered in the accession ledger in the mid-19th century, and will inevitably reflect the attitudes of those days.

If you continue through to the Pitt Rivers Collections Online catalogue you will find a standard ‘search’ box. Since the mask at the centre of the Telegraph article was a product of the Igbo people, I searched by ‘Igbo’. The results (image above) are fairly typical of online collection searches. The search produced a list, with images and details. A series of filters (on the left side in the image below,) allow you to limit the results according to various criteria (I set my filters to only show records with photographs). Various buttons allow you to change the format of the results (I set mine to ‘gallery’).

Cultural sensitivity

‘The Pitt Rivers cultural sensitivity pop-up indicates that the museum wishes visitors to be aware of when an object is ‘culturally sensitive’. The pop-up does not give a clear definition, but from the context ‘culturally sensitive’ objects seem to include; objects associated with private rituals or ceremonies; objects showing or recording the dead; and, perhaps although this is not entirely clear from the pop-up, objects described using outdated science and offensive language. As I mentioned in the previous post, it’s very obvious that the Pitt Rivers Museum wants to offer its visitors the option to explicitly consent via opt-in, to seeing such ‘culturally sensitive’ objects.

Clear messaging

I had to scroll through 10 pages of results before I found an Igbo item with a photograph and a cultural sensitivity warning, and I could still see it if I clicked ‘show’ (Collections Online image above, bottom left object in the screengrab).

Most of the objects without photographs simply haven’t been digitised yet. This is stated clearly in the online catalogue with the label, ‘We have not yet digitised this object’. Checking, revising, updating and improving object catalogues and their online versions with improved information and object photographs is time-consuming and expensive, and most museums have not managed to digitise their entire collection yet. This is not a conspiracy but is due to a lack of funds. Local and central government funding is limited and private or corporate donors are often more interested in gallery redisplays and sponsoring exhibitions.

Now, there are some objects at the Pitt Rivers where digital images exist but are not available to the public. Madeline Odent (@oldenoughtosay) found at least one object where the sensitivity warning advises the user ‘This object has been digitised but we are unable to show the media publically. Please contact the museum for more information’ (See embedded twitter thread, above right). Much like the tsanta, which have been removed from their display case in the gallery, this is about public display. The tsantsa have been removed to prevent unintentional viewing by the public, and certain objects have their photographs restricted for the same reason. As Madeline Odent puts it, ‘What you can no longer do is gawp at human remains!’

This is an explicit effort to push back against an idea ingrained in the historic Wunderkammer concept, that it’s reasonable to come and stare at artefacts, especially human remains, from another culture. So the Pitt Rivers Museum has changed its policies, so that those who need to see the tsantsa or the Igbo mask, can contact the curators and make an appointment.

Researcher visits

The ability to contact curators or collections managers and obtain access to photographs, catalogue records and/or visit in person to see and work with objects is a really important part of most museums. People with a genuine interest can arrange a visit with the curator or curatorial team to examine, record and even photograph an object. Sometimes they might have to wait until an object comes back from a travelling exhibition, and sometimes they might need to be able to demonstrate their research interest through a letter from their institution (although that is less commonly required these days). For the most part, if you have a research interest in something serious enough to arrange a visit and travel to a museum, you can see pretty much whatever you need to. Again this is the logic which underpins the statement in the Pitt Rivers response to the Telegraph article, ‘that no one had ever been denied access to it [the Igbo mask]’. With this statement, they are asserting that, as with many other objects in storage in museums, access can be provided and that the Igbo mask is no different from the many other objects accessible to researchers on request.

Changing narratives

The Pitt Rivers Museum is apparently keeping its Wunderkammer-style, and the changes it is making can be understood as part of the effort to enable visitors to follow myriad narratives through its vast array of objects. The cultural sensitivity warnings, shift to requiring explicit consent from the digital visitor via opt-in, and the inclusion of additional signage in the five display cases identified by Madeline Odent in the Twitter thread of her visit, all reveal a curatorial team intending to provide additional context and further background for the visitor. Such contexts can enhance the visitor experience, by helping them avoid images they might find distressing or inappropriate. In a visit to a Wunderkammer-style museum, it is almost impossible to give every object and case an equal viewing. The visitor ends up picking and choosing those cases and objects which interest them. In a previous post about Wunderkammer museums, I posited that the sheer range of objects in such as museum offered the possibility for visitors to craft a wider range of narratives from a greater variety of perspectives, than in a more modern pared-down display. In providing additional signage, and information about the origins of the collection and the objects within it, the Pitt Rivers Museum is giving visitors additional tools to do exactly that!

Acknowledgements

Huge thanks to Madeline Odent for giving her explicit consent for me to use her tweets in this piece. Do please go and check out @oldenoughtosay on the platform formerly known as Twitter.

Find out more

Related posts

-

Stonehenge Tunnel – a Planning Archaeologist’s Perspective

-

Stonehenge and planning archaeology in England

Thanks so much for this excellent post about the complexities of displaying artefacts and especially human remains in today’s world.

Pingback: Weaponising women: How an article about women’s rights and access is really a criticism of decolonisation. – Scribe in the House of Life: Hannah Pethen Ph.D.