In my previous post, I reviewed the Grand Egyptian Museum atrium and Tutankhamun: The Immersive Experience. In this post I will address the sculptures of the Grand Staircase, the only display of ancient Egyptian artefacts currently accessible to the visitor, apart from the statues in the atrium and the hanging obelisk. When the museum is fully open, the Grand Staircase will lead to the galleries of museum exhibits, but at the time of writing (February 2024) it can be visited as part of a guided tour that also includes the hanging obelisk and the atrium and follows the immersive Tutankhamun experience. Tickets can be booked via the GEM website.

Practicalities

The Grand Staircase is located in the centre of the south side of the GEM, and is accessed by turnstiles in front of the granite statues of two Ptolemaic monarchs (probably Ptolemy II and Arsinoe II). There are four travelators to the right of the staircase, allowing visitors to ride up and access three intermediate landings and the top level of the staircase. For those with accessibilty needs the travelator will be most welcome, but there is nothing to stop you from walking up, and the stairs are interspersed with seating if you need a rest, or would like to stop and soak in the statuary and sculptures. Each landing has a large board explaining the theme of the next part of the staircase, and touchable models of significant artefacts for those who need tactile formats. Spaced regularly up the staircase, with easy access all around the individual artefacts, the statuary renders the staircase a kind of vertical sculpture gallery.

The royal image

The sculptures of the Grand Staircase are broadly themed around Kingship, beginning with various royal statues, followed by sculptures showing the relationship between the King and the gods, and ending with those relating to the royal afterlife. In the lowest section of the staircase, we are introduced to various Pharaohs, beginning with an unfortunate late Middle Kingdom Pharaoh (probably Sensuret III or Amenemhat IV) whose pair of seated colossal statues were usurped initially by Ramses II and now bear the cartouches of Merneptah. Several statues of Thutmose III, Hatshepsut, and a rather nice black granite seated statue of Amenhotep III serve to represent the Thutmosides. The Ramessides are represented by three standard bearers of Merenptah, Seti II (usurped from Amenmesse), and Ramses III, but don’t worry there’s plenty of Ramses II to come! Then we jump to the Roman period with a statue of Emperor Caracalla as Pharoah. This is not a chronological introduction to the Pharaohs. Despite some beautiful royal statuary elsewhere, several major periods are not represented. Instead, this lower section reads as an introduction to the range of royal statuary that is not represented throughout the rest of the staircase.

There is considerable artistry in the layout of the statues on the stairs, with juxtapositions that are periodically Egyptologically apposite. I’m sure the conventionally religious Pharaohs would approve of their separation from the colossal head of Akhenaten, which sits on the western side of the staircase, next to the travellator. A statue of Hatshepsut as Pharaoh stands alongside and below one of Thutmose III, usurped from her. Viewing these two statues side-by-side reveals the similarity in style and facial features. Interestingly, although the statue of Hatshepsut is located on a lower step, she has a much bigger plinth, with the effect that her statue rises higher than that of Thutmose III. It is sleight of hand worthy of Khafre!

At the first landing, you can divert left to view the Saqqara King List (GEM 45485), and the 10 painted limestone statues of Senusret I from his pyramid complex at Lisht. The Saqqara King List is beautifully laid out, with a detailed explanatory diagram of every cartouche, although it is rather difficult to photograph effectively. The 10 statues of Senurest I are individually stunning and laid out up the stairs as a triangle, with four statues on the lowest stage, then three, two, and one. The arrangement will be particularly impressive when viewed from the atrium, although when I visited it was obscured by seating and audio-visual equipment for an event.

King and gods

Beyond the first landing, the sculptures change to reflect the relationship of the King with the gods. Here the sculptures begin to include carved architectural elements created by various pharaohs to adorn the temples of their gods: naoi; palmiform and papyriform pillars, some with lintels; an offering table of Amenemhat VI; and an obelisk tip of Hatshepsut all attest to the varied uses of stone in ancient Egyptian religious culture. It was a pleasure to see architectural elements from both the Old and Middle Kingdom including beautiful palmiform columns (two of which came from the pyramid temple of Sahure at Abusir), a naos of Sensuret I (GEM 1670), and the Second Intermediate Period papyriform pillars and lintel from Medamud (GEM 6779), originally dedicated by Sobekhotep III and reinscribed for Sobekemsaf I.

An interesting naos of Ramses II bridges the gap between architecture and divine imagery (GEM 7826). It is formed like a free-standing rock-cut chapel, with a barrel-vaulted roof, and three divine images carved out of the rock forming the rear interior wall of the naos. This naos is incredibly Ramesside in style, almost a miniature version of the sanctuary at Abu Simbel. Those who are familiar with Ramesside rock-cut temples will not be surprised to learn that Ramses II (as Khepri) is himself represented amongst the three divine statues carved out of the rear interior wall. Interestingly, this naos came from Tanis and was perhaps originally erected at Piramesse, both places which belong to a very different Deltaic tradition and lack the natural geography for rock-cut temples.

The naos of Ramses II heralds a change in theme beyond the second landing. The sculpture is now dominated by statues of the gods, donated by loyal Pharaohs, who sometimes feature as co-deities. As you can see from the following image Ramses II features heavily, as do northern sites like Tanis (San el-Hagar), Memphis (Mit Rahina), Herakleopolis Magna (Ihnasya el-Medina). The only exceptions to this are an Osiride statue of Senusret I from Abydos and several statues from Luxor, mostly from the Amenhotep III mortuary temple at Kom el-Hetan. What unites all these sites is that most of them have been under excavation recently. It seems likely that recent excavations have contributed many objects to the Grand Staircase, either directly or through background research in museum and site stores, but the object labels do not confirm the excat circumstances of discovery. I find this a little unfortunate from a research perspective, since noting such circumstances on object labels makes it much easier to find the relevant excavation reports and exact details of an object’s archaeological context.

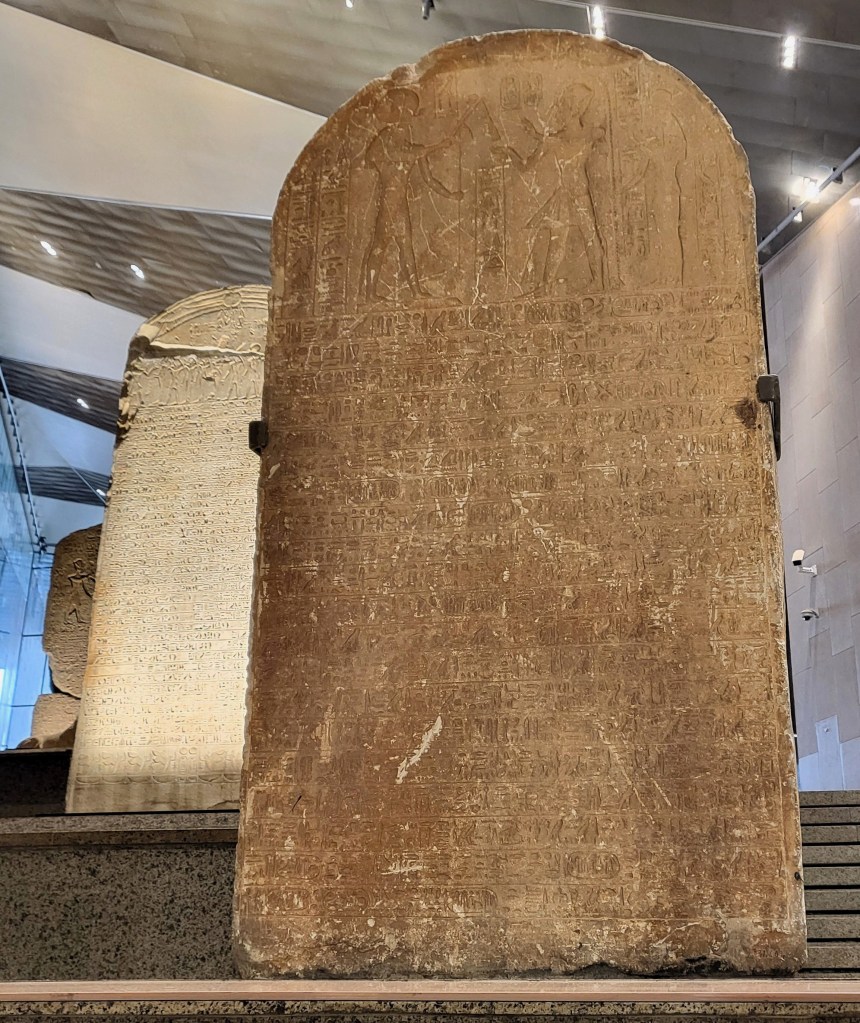

Juts before the third landing, we are treated to an explosion of stelae, as royal interaction with the divine takes a verbal turn. In addition to the three stelae shown in the previous image, and one of Akhenaton reinscribed by Horemheb (GEM 5853), there is a fascinating stela of Ramses II in the traditional style of a quarrying stela. The stela (GEM 8249) tells how Ramses II found a huge quartzite rock while ‘strolling’ in the desert countryside opposite ‘Hathor, Lady of the Red Mountain’ and rewarded the skilled workers who carved it and others. The desert location, framing of the event as a ‘chance discovery’, and the references to ‘Hathor, Lady of the red Mountain’, all place this stela firmly in the quarry-stela tradition, emphasising the favour of the gods towards the Pharaoh and his dominance over the desert ‘god’s land’, that produces precious metals and stones. Similar sentiments can be found in the stelae from quarry sites at Serabit el-Khadim, Wadi Hammmat, Gebel el-Asr and Wadi el-Hudi amongst others.

Funerary sculpture

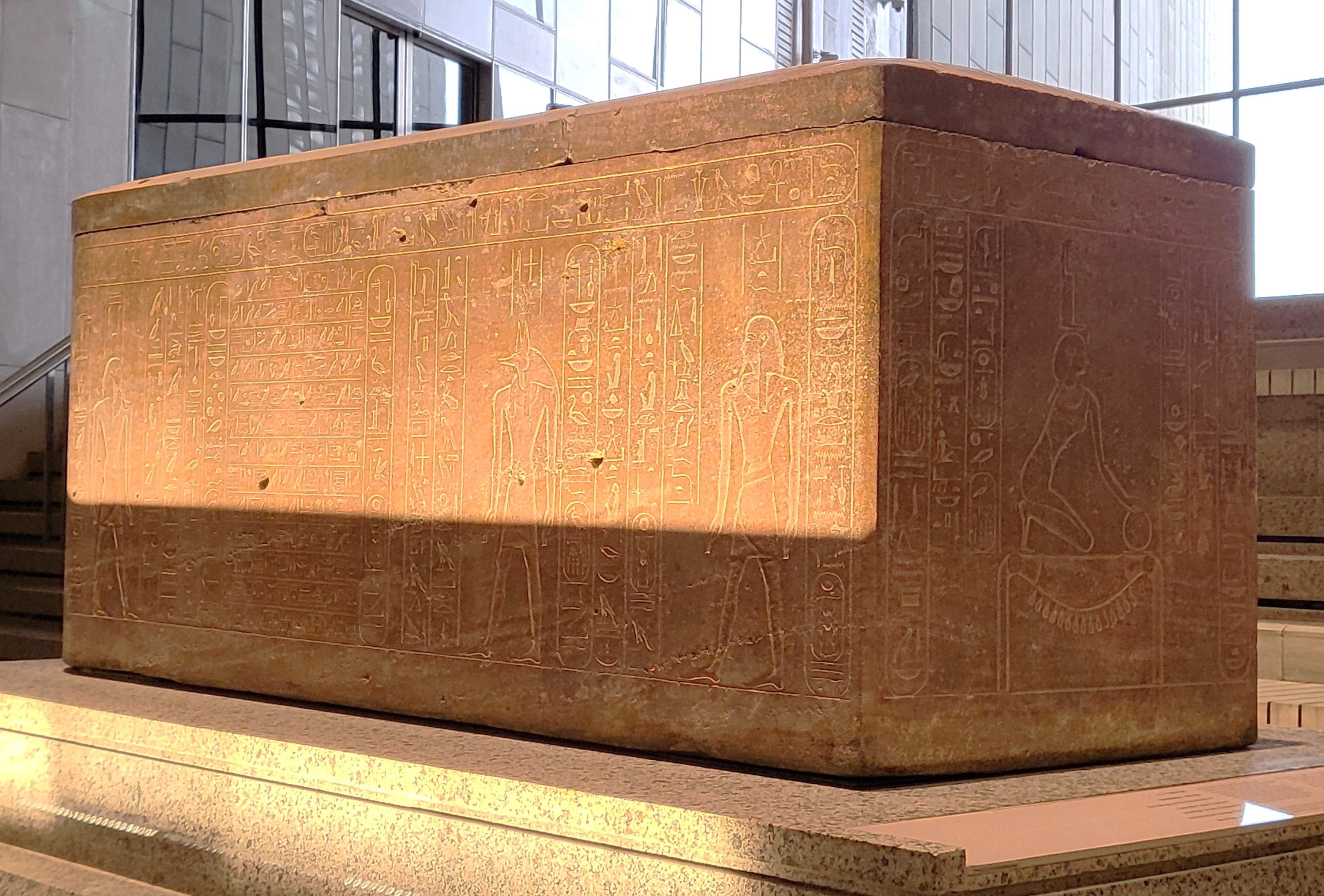

The final section of the staircase is funerary in nature, with beautiful examples of stone sarcophagi from throughout Egyptian history and a lonely 13th Dynasty pyramidion of an unknown King from Saqqara. The display, like the whole of the Grand Staircase and atrium, is beautifully lit in an artistic style that highlights certain features of the statuary. This makes for artistic photographs but might frustrate those seeking obscure details of text and sculpture that can be hidden in shadow. The beautiful sarcophagus of Thutmose I (GEM 45944) created for him by his grandson Thutmose III and found in KV38, is a classic case in point. The sarcophagus is beautifully and artfully lit, but the lower part is in shadow, while the upper part is strongly lit. It is possible to improve the contrast between the two sections, allowing the lower part of the inscriptions to be read, but this does require some adjustment in image processing. The two images below show the sarcophagus as first photographed, and after adjustment in an image processing programme.

At the end of the staircase is the final landing with a stunning view of the pyramid of Khafre and a model of how the entire GEM complex will look once its been completed. The upcoming hotel, which will be built between the GEM and the Giza pyramids, reflects the desire for the GEM/Giza ensemble to become a central place for ancient Egyptian culture, where you can visit the last wonder of the ancient world, and see the greatest treasures of ancient Egypt, including those of Tutankhamun, without crossing Cairo to the museum on Tahrir Square. The Giza/GEM combination will make for a fascinating introduction to Egypt, but I hope that visitors will still take time to visit the other ancient Egyptian, Coptic and Islamic sites in the Cairo area.

References

The descriptions of the artefacts are mostly taken from the excellent object labels.

My summary of the rather complex tradition of quarrying inscriptions and the underlying mythology is drawn from:

- Aufrère, S. 1991, L’Univers Minéral dans la Pensée Égyptienne. IFAO; Cairo.

- Blumenthal, E. 1977. “Die Textgattung Expeditionsbericht in Ägypten.” In: J. Assmann, E. Feucht and R. Grieshammer (eds.) Fragen and die Altägyptische Literatur: Studien zum Gedenken an Eberhard Otto. 86-118.

- Darnell, J. and Manassa, C. 2013. “A trustworthy seal-bearer on a mission: The monuments of Sabastet from the Khephren Diorite Quarries.” In: H. Fischer-Elfert and R. B. Parkinson (eds), Studies on the Middle Kingdom in memory of Detlef Franke, Harrassowitz; Wiesbaden. 55–92.

- Eichler. E. 1994. “Zur kultischen Bedeutung von Expeditionsinschriften.” In: B. M. Bryan and D. Lorton (eds.). Essays in Egyptology in Honour of Hans Goedicke. 69-80.

- Pethen, H. 2014. “The Pharaoh as Horus: Three dimensional figurines from mining sites and the religious context for the extraction of minerals in the Middle Kingdom.” In: T. Lekov, and E. Buzov, (eds.) Cult and Belief in Ancient Egypt: Proceedings of the Fourth International Congress for Young Egyptologists 22-25 September 2012, Sofia, Bulgaria. Bulgarian Institute of Egyptology.151–162.

- Valbelle, D. & Bonnet, C. 1996. Le sanctuaire d’Hathor maîtresse de la turquoise. Picard Editeur; Paris.

For more information on the several sarcophaguses and post-mortem movement of Thutmose I during the reigns of Thutmose II, Hatshepsut and Thutmose III, please see;

- Der Maneulian, P. and Loeben, C. E. 1993. “From Daughter to Father: The recarved Egyptian sarcophagus of Queen Hatshepsut and King Thutmose I” Journal of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. 5:24-60. <http://www.gizapyramids.org/static/pdf%20library/bmfa_pdfs/jmfa05_1993_24to61.pdf>

Image repository

I’ve now upgraded my Flickr account to house all the photos I take during visits to museums, galleries, and sites. Over the coming months, I’ll be uploading more of my images, and editing those already on the site, but you can now view all my images from the visit to the Grand Egyptian Museum in February 2024. All the images are posted on an ‘Attribution – Non-commercial’ license so you are welcome to download and make use of them on that basis. The title of each photo contains essential information, including what it is, where it was found, what it is made of, and its museum number, where these are known. Additional information can be found in the description section for each image, and they are also tagged extensively.

Find out more

Related posts

-

Wunderkammers, colonial hangovers and multivocality.

-

Egyptian Artefacts in the Southend Museum

Pingback: Grand Egyptian Museum: Grand Staircase Review – The Pursuits of Porsha

Pingback: Visiting the tomb of Meresankh III, Eastern Cemetery, Giza G7530-G7540 – Scribe in the House of Life: Hannah Pethen Ph.D.

Pingback: Grand Egyptian Museum (GEM) – Joni's Jottings