NOTE: This post includes mentions and some distant images of mummified people (sahw).

In February 2023, the Manchester Museum reopened following a major refit. In April I visited the museum, including the refurbished Egypt and Sudan Gallery, and the Golden Mummies exhibition. The museum is open from 10am Tuesday to Friday and Sunday (from 8am on Saturday) and closes at 5pm every day except Wednesday when closing is 9pm.

The Egypt and Sudan Gallery is a relatively small space on the first floor of the museum. Despite its size, the display is weighty, both in terms of the objects and the interpretation provided in the new signage. All the objects are displayed alongside their object numbers, although I found some of the signage a little confusing. Amidst the new display and signage, old favourites are still present; several people on Facebook were delighted to learn that a three-dimensional display of amulets, showing how they would be located within a sahw (mummified person), could still be found in the gallery (first image).

Chronology

Like most displays of ancient Egyptian material, the gallery includes both chronological and thematic elements to orientate the visitor as to the history and culture of ancient Egypt. While the chronological material is relatively typical for a display of this type, it does include a number of fascinating objects. There are the unusual sunken paste reliefs of the mastaba of Nefermaat and Itet at Meidum (Manchester Museum #5168 and #3594); and a beautiful shell-shaped palette (Manchester Museum #1695). Although the object label describes it as ‘diorite’ this shell palette is unmistakably anorthosite gneiss from the Gebel el-Asr quarries, which is often erroneously described as ‘diorite’. Another fascinating and important object is the linen and plaster mask, possibly of Bes or Aha (Manchester Museum #123), found at the town of Kahun , which shows signs of having been worn in life and may be a piece of ritual equipment (Horváth 2015).

Themes

The major theme of Egypt and Sudan is the ancient Egyptian way of death. This is hardly surprising. Manchester has long had a strong interest in Egyptian mummification, ranging from Margaret Murray‘s ‘scientific’ unwrapping of Khnum-Nakht at Manchester in 1908, to the Manchester Mummy Project of the late 20th century and the current Golden Mummies exhibition. Furthermore, like many museums, much of Manchester’s collection was created during the late 19th and early 20th century, when desert cemeteries were a major focus of both archaeological excavations and antiquities hunters. As a result, the vast majority of objects in such collections relate to tombs, graves, and sahw with the occasional temple fragment, royal or noble statue. The common perception that ancient Egypt was a culture obsessed with death is inaccurate, but it reflects a very real bias towards tombs and cemeteries in both historic excavations and museum collections. Manchester Museum is no exception.

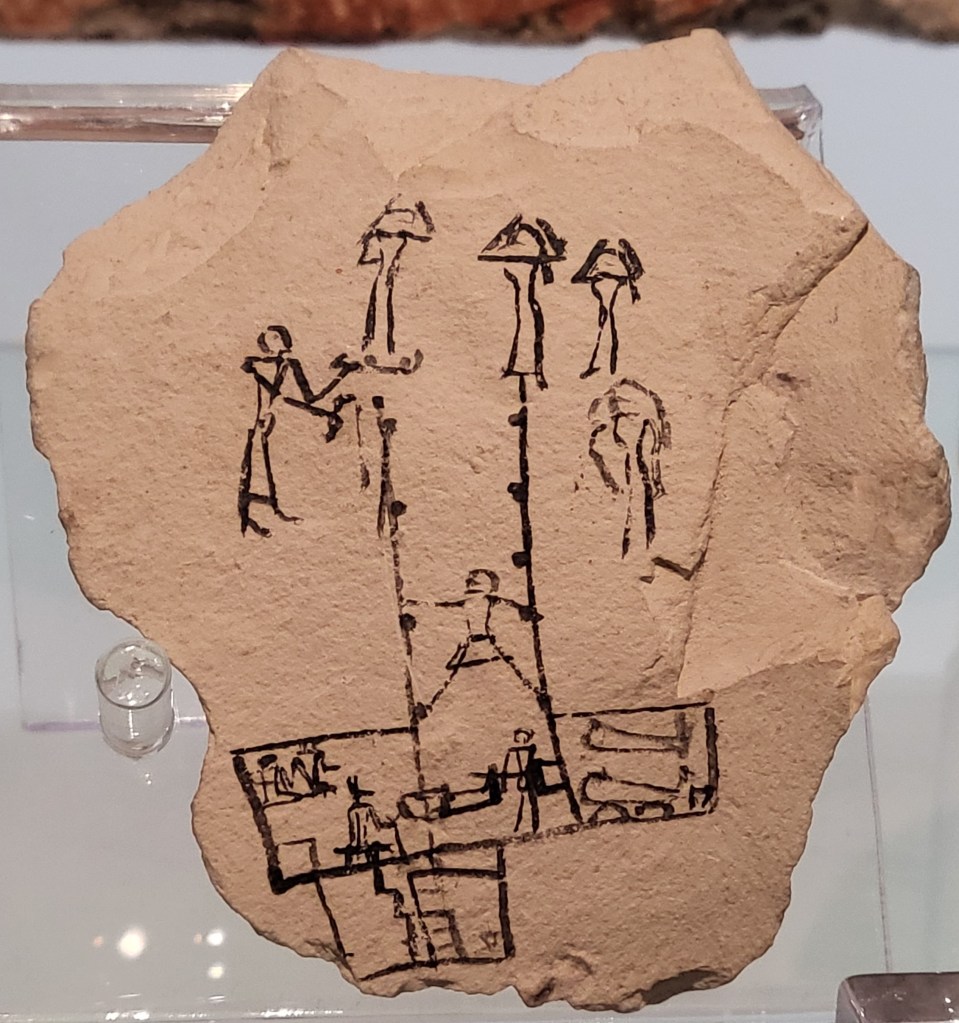

Nevertheless, the redisplay shows a determined effort to highlight the significant, unusual and important aspects of the collection, as well as the ‘usual suspects’, objects which are typically found in most ancient Egyptian collections (late-period bronze statues of gods, stelae, coffins, ushabtis, statues, wooden models and sahw). The royal statues on display also include less common examples, such as a part-statue of Ramses II wearing the atef crown, his head embraced by the Horus falcon (Manchester Museum #1783). The ostracon showing a burial (Manchester Museum #5886) is an unusual and fascinating object, that although related to ancient Egypt burial customs, is anything but common.

A large case in the centre left of the gallery contains the entire assemblage from the tomb of the two brothers at Rifeh; including Nakht-ankh and Khnum-hotep’s coffins, Nakht-ankh’s canopic chest, five statues and two model boats (David 2007). The accompanying label discusses the history of the tomb group, its excavation, the unwrapping of the two men as part of Manchester’s developing interest in mummification, and the scientific racism associated with early discussions around the men’s identities. Honest discussions of the negative history of the collection, in terms of scientific racism and voyeurism, feature on several of the new signs.

Ethics

The new signage also reflects current thinking about ethics and museums. The unwrapped sahw of Asru is on display, decorously covered with a sheet and mostly hidden beneath the upper part of her coffin. After a description of the unwrapping and investigation of Asru over the centuries, the associated signage states that ‘Asru’s body has been at least partly visible on public display for around two hundred years. She is currently the only person whose mummified remains are visible in the Manchester Museum. As we think through what being a caring museum means, she may be the last.’ While I can’t love the use of ‘mummified remains’ (as I have previously discussed), it’s refreshing to see honest signage about how curators are working with the ethical issues surrounding their collections.

In a similar vein, the Archaeology gallery, adjacent to Egypt and Sudan, uses a wide range of artefacts from all over Europe, North Africa and the Middle East to consider the movement and migration of both people and objects. As at nearby Liverpool, Manchester funded excavations in Egypt in the late 19th, and early 20th century, and received many objects from these excavations in return as part of the colonial partage scheme (see also Abd el Gawad and Stevenson 2021). The display includes an interesting array of predynastic pots excavated by Flinders Petrie, which formed part of his sequence dating corpus. The pots are displayed alongside Petrie’s excavation reports, open to pages showing drawings of the same artefacts. Such objects nestle alongside locally excavated British artefacts, ancient trade goods, and narratives of modern forced migration showing how people and artefacts have always moved and disrupting the traditional geographical classifications of artefacts and cultures.

Balance

Redisplaying a permanent gallery in the 2020s is a difficult prospect, requiring balancing multiple visitor expectations with ethical dilemmas resulting from the history of the discipline and the origins of the artefacts. Overall, the Egypt and Sudan Gallery at Manchester Museum suceeds very well. The chronological and thematic displays cover the essentials of ancient Egyptian culture, making good use of the many important artefacts in the collection. The bias towards death and burial, while real, should not be read as a criticism of the display, but rather as a feature inherent to its origins. If I have one criticism it is that the re-display could have made more use of the many excavated artefacts to emphasise the importance of archaeological context: in particular, the complete tomb assemblage of Nakht-ankh and Khnum-hotep represents an opportunity to explore the physical, archaeological and landscape context of a complete tomb assemblage. There is a sad lack of public awareness about the importance of archaeological context in general, which directly feeds into many misconceptions about the purpose and nature of archaeological excavation. This is particularly acute for ancient Egyptian material, where many outdated stereotypes abound.

One aspect of the redisplay which has been particularly successful is its honest discussion of the ethical issues inherent in the history, investigation and display of the sahw of Asru and the two brothers. As museology and Egyptology begin to address questions colonialism, racism and orientalism more widely, honest labelling around these issue will hopefully become more common. Inevitably it won’t be enough for some, and too much for others, but that is the challenge! Balancing visitor expectations, ethical considerations and museological change is never straightforward, but the combination in the Egypt and Sudan Gallery is nicely managed, particularly with the adjacent Archaeology Gallery providing further global context for object movement.

References

Abd el-Gawad, H. and Stevenson, A. 2021. ‘Egypt’s dispersed heritage: Multidirectional storytelling through comic art’ Journal of Social Archaeology 21(1): 121-145. DOI: 10.1177/1469605321992929

David, R. 2007. The Two Brothers. Death and the afterlife in Ancient Egypt. Rutherford Press.

Horváth, Z. 2015. ‘Hathor and her Festivals at Lahun’, In: Miniaci, Grajetzki (ed.), The World of Middle Kingdom Egypt (2000-1550 BC) I, MKS 1, London, 125-144.

Robinson, P. 2003. ‘”As for them That Know, they Shall Find their Paths”: Speculations on Ritual Landscapes in the ‘Book of Two Ways.’’ In: David O’Connor, and Stephen Quirke, (eds). Mysterious Lands. London: University College London Press. 139–160.

Find out more

Related posts

-

Grand Egyptian Museum Atrium and Immersive Tutankhamun: Review

-

Review of the re-displayed Egypt and Sudan gallery of the Manchester Museum

-

What sahw you? ‘Mummies’, ‘Mummified people’ or ‘Mummified remains’?