For anyone who’s been hiding under a rock, 2022 was a big year for Egyptology: the anniversary of the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun in 1922, and the bicentenary of the first publication announcing the decipherment of Hieroglyphs in 1822. Institutions have chosen which anniversary to celebrate, resulting in a plethora of exhibitions and other events related to Tutankhamun, Hieroglyphs, and Egypt. Many British institutions have chosen to focus on Tutankhamun, approached in a variety of different ways from the Griffith Institute’s Tutankhamun: Excavating the Archive to the Sainsbury Centre’s Visions of Ancient Egypt, and the Petrie Museum’s Tutankhamun: the Boy, which I review in next month’s post. In contrast, the British Museum’s current exhibition Hieroglyphs: unlocking ancient Egypt (13 October 2022 to 19 February 2023) covers the bicentenary of the decipherment of Hieroglyphs. The exhibition is accompanied by a glossy catalogue including many excellent images of the artefacts and insightful essays about everything from How Hieroglyphs Work to Egyptian Identity.

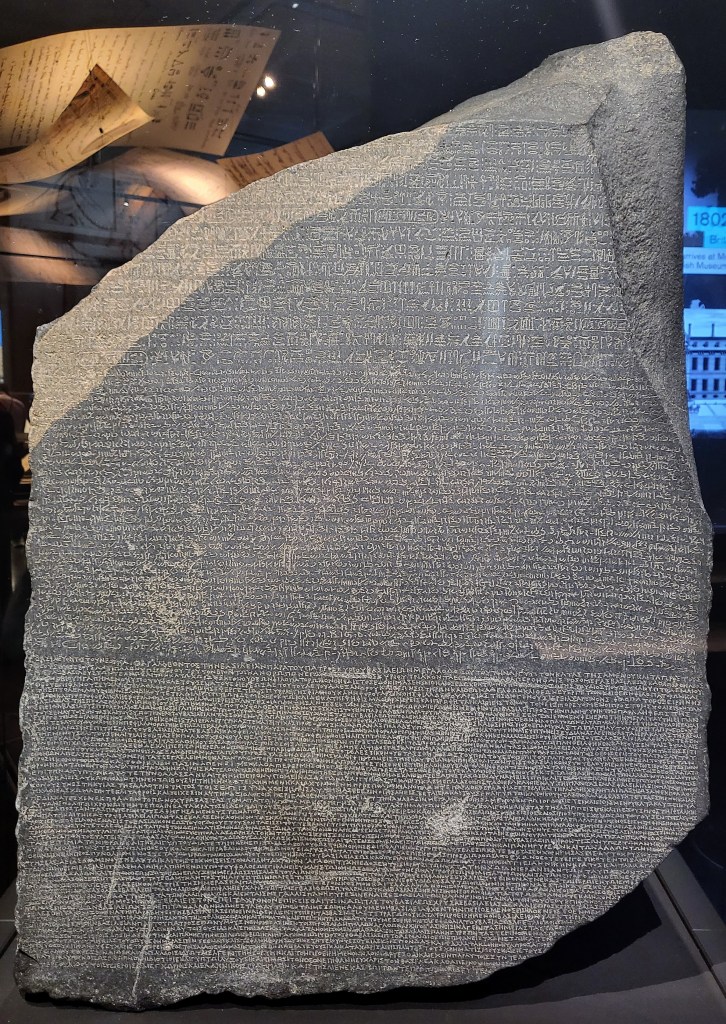

Rosetta Stone

It is hardly surprising that the British Museum should choose to focus on the bicentenary of the decipherment of Hieroglyphs given that it is the home of the Rosetta Stone (Hagar Rashid in Arabic), discovered in 1799 during construction work at Rosetta/Rashid fort and ceded to the British following the defeat of Napoleon’s forces. With its trilingual inscription, in Hieroglyphs, Demotic, and Greek, the Rosetta Stone provided the key to understanding both the ancient Egyptian language and its unique scripts. As such the Rosetta Stone is a key touchstone (quite literally) for Egyptology and the subject of controversy with many calls for its repatriation to Egypt, and a proposal that it should be displayed in the new Grand Egyptian Museum at Giza.

The Rosetta Stone is a centrepiece of the Hieroglyphs exhibition and it was a pleasure to see it clearly, out of the glass case in the Egyptian Sculpture Gallery where it normally resides. As the source of the inscription that made decipherment possible, the Rosetta Stone has its own section covering the political and geographical context for its discovery, its origins, and its content. The exhibition even manages to arouse interest in the text on the Rosetta Stone, the Memphite Decree. The Memphite Decree is a relatively ordinary valediction of Pharaoh Ptolemy V from 196 BC which was sent out across Egypt and incised on various stones set up in multiple locations. The exhibition covers this fairly mundane text in a fascinating section on the Rosetta Stone’s ‘family tree’, including other versions of the Memphite Decree and its antecedents dating right back to 243 BC.

History of decipherment

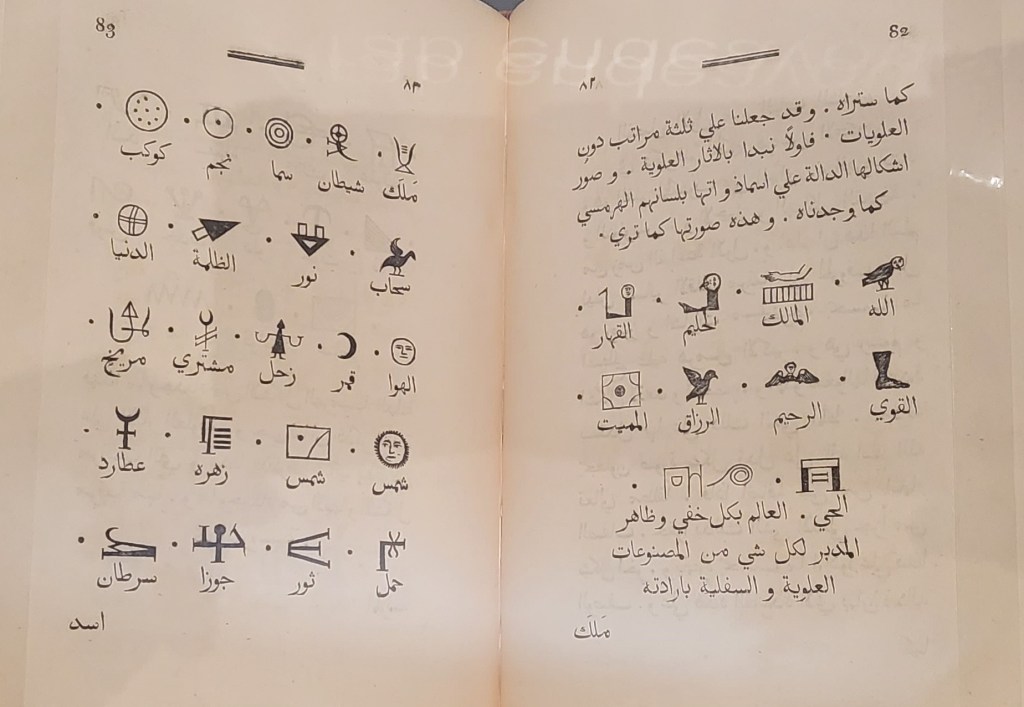

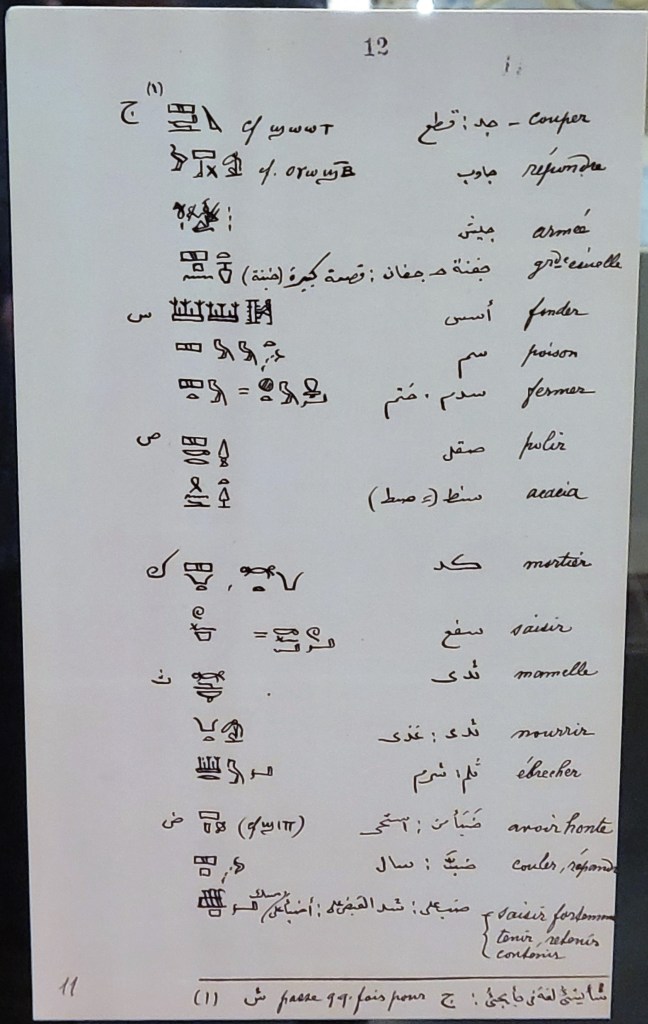

The exhibition is divided into three parts: early attempts to understand hieroglyphs, including the Arabic authors who contributed to the decipherment process; the discovery of the Rosetta Stone and the process of decipherment; and the impact of the discovery in terms of the understanding of ancient Egyptian written culture. The first two parts are distinctly chronological and work extremely well. Although the Londonist’s reviewer thought the exhibition got ‘bogged down’ by the in-depth discussions of the process of decipherment, I feel that this detailed understanding of the process is not only the point of the exhibition, but also vital to understanding the complexity of decipherment and the many people who contributed. We follow engagement with Hieroglyphs by Arabic and European scholars, Renaissance interest and collecting, the Napoleonic expedition and discovery of the Rosetta Stone, and the process of decipherment, including the competition between Thomas Young and Jean-François Champollion. Objects relevant to these subjects are interspersed by hieroglyphic artefacts, such as the ‘magical’ sarcophagus of Hapmen (British Museum EA 23), the statue of Pa-Maj covered with magical texts (National Archaeological Museum of Naples 1065), and even a pseudo-hieroglyphic fake made in Italy in the 18th century (Civic Archaeological Museum of Bologna EG 3707).

After the section covering the Rosetta Stone, its discovery, text and ‘family tree’ we learn how Young and Champollion used the text to understand ancient Egyptian languages. From early-19th-century methods of copying the Rosetta Stone’s text, we progress to the various approaches and discussions of Young and Champollion as they wrestled with the unfamiliar text. This is a fascinating view of the difficulties, dead-ends, leads, collaborations and competitiveness of the process of decipherment. In terms of presentation, the exhibition offers the opportunity to bring related objects together, such as the presentation of artefacts and the drawings of those artefacts in books used by Champollion. Normally books and artefacts are kept separately so seeing these objects together is a real treat. This section also includes Coptic chanting, representing Champollion’s relationship with the Coptic community in Paris and the importance of the Coptic language in his work. The chanting is an interesting method of including some additional sensory input, but it is unfortunate that it is audible beyond the section on Champollion’s study of Coptic where it is most logical. Since the chant is audible from the first room of the exhibition, the visitor spends a while confused as to its purpose before getting to the relevant section. It’s hardly surprising that several people mentioned that they found it a little repetitive. This type of situation could perhaps benefit from the type of directed audio used by the Wunderkammer exhibition to ensure relevant soundscapes are only audible within certain spaces.

In addition to the members of the Coptic community in Paris, the exhibition acknowledges others who collaborated with Champollion and contributed to his success, including providing him with images and copies of hieroglyphic inscriptions. In this way, and in its inclusion of Young, the exhibition pushes back against the ‘Great Man’ theory, in which discoveries, changes and developments are ascribed to lone, typically white, male, elite innovators while everyone else involved is whitewashed out. Champollion certainly made significant advances, but he had considerable help from a wide range of others, many of whom appear in the exhibition.

Royal writing

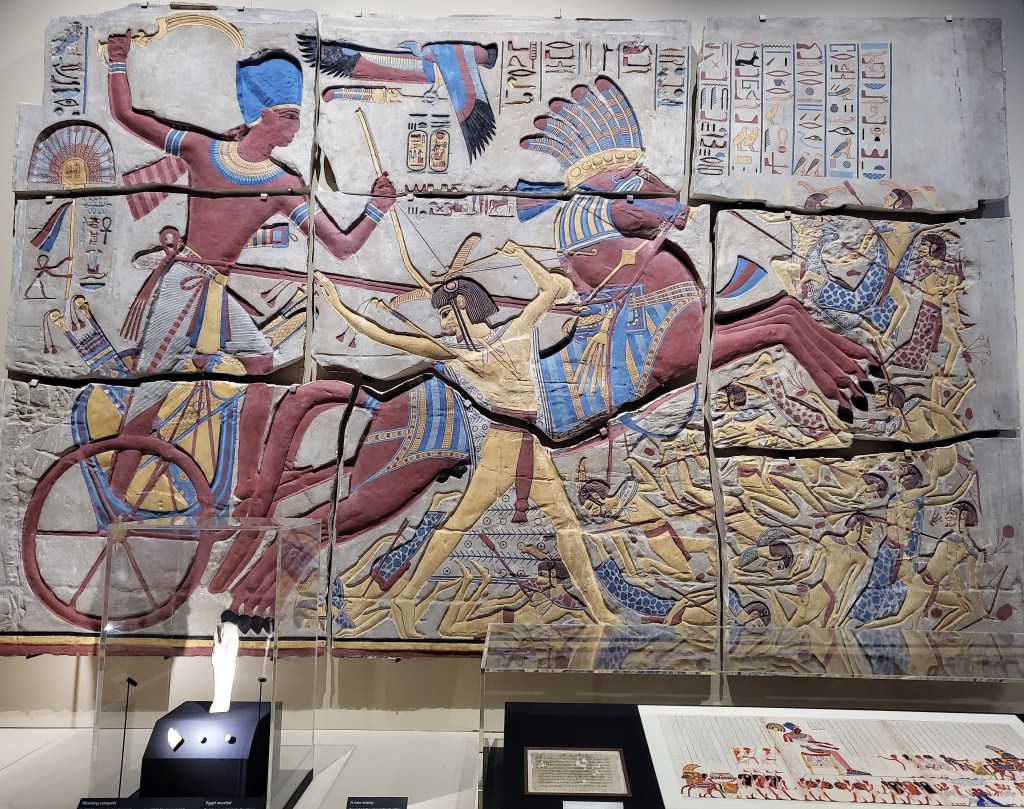

After covering the process of decipherment, the exhibition broadens out to become a more general view of the nature of ancient Egyptian written culture. It begins with royal uses of writing before expanding to cover the range of Egyptian written culture. In the process, it features various important artefacts from the British Museum collection, many of which are not on permanent display in the galleries. Our introduction to royal writing begins with the Abydos King List, (British Museum EA 117), a list of all approved ancient Egyptian Pharaohs from the temple of Ramesses II at Abydos. The King List is normally on display in the Egyptian galleries but is particularly beautifully lit in the exhibition and attracted a lot of attention. Several of those examining it while I visited were disappointed that the exhibition did not explain in more detail how the Hieroglyphic script works. Detailed explanations of how to read hieroglyphs are obviously too much for an exhibition, but the large size of the King List, the relative simplicity of royal cartouches and their importance in Champollion’s decipherment presented a missed opportunity to explain how the signs combine to produce the royal names. This could have been achieved in a similar style to the explanations situated around the Book of the Dead of Nedjmet (British Museum EA 10541), where the papyrus is located in the centre of the panel, with explanations in the large backlit border around it.

After the King List the section on royalty continues with the stunning beautifully coloured plaster casts (BM EA 91038a-o) of the northern exterior wall of the hypostyle hall of the temple of Karnak, featuring Seti I ‘smiting’ the Libyans and a similar scene from almost 2000 years earlier showing First Dynasty King Den smiting an enemy on an ivory label. Royal statues, inscriptions and obelisks further reflect the royal uses of hieroglyphs.

Reading Egyptian written culture

A wider view of Egyptian written culture follows and there are many other showstoppers in this part of the exhibition. The small sphinx (BM EA 41748) with its early alphabetic proto-Sinaitic script from Serabit el-Khadim is not only a famous and important object but also of direct relevance to the subject of Egyptian scripts.

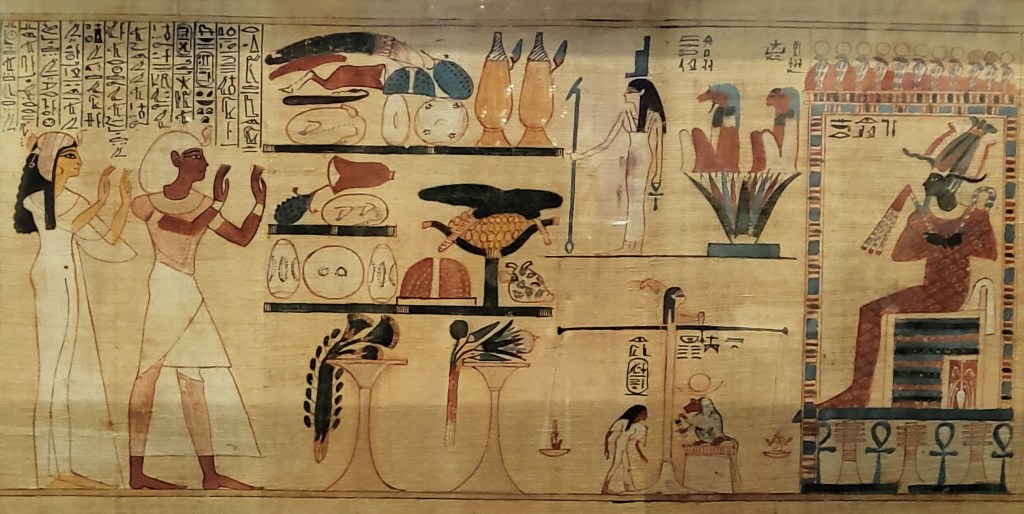

Papyri are rarely on display for long, owing to the need to preserve their delicate pigments and Nedjemt’s (BM EA 10490) is one of the most beautifully illustrated, so its inclusion in this exhibition is a treat. As if that were not enough, it is a masterclass in interpretation. Funerary papyri contain an incredible amount of detail, linking to complex theological, sociological and political aspects of Egyptian society. It would be easy to overwhelm the visitor. But the interpretation of Nedjemet’s papyrus is as perfectly balanced as an honest heart weighed on the scales of Djehuty. We are even given a little background information about Nedjmet’s probable involvement in the murder of two policemen – making this papyrus a true test of the efficacy of Egyptian magic. With such a sin on her heart, this papyrus would have to be powerful indeed to make it weigh less than the feather of truth.

This part of the exhibition contains many other papyrological treasures, rarely exhibited for their own protection: the dream papyrus (BM EA 10683); the Tale of the Eloquent Peasant (BM EA 10274); and the Rhind Mathematical Papyrus with the first approximation of Pi (BM EA 10057-58). The Shabaquo Stone is also on display. There are also examples of many typical ancient Egyptian objects: including ancestor busts; mummy tags; funerary stelae; mummy cartonnage; canopic jars; ostraca; block and scribal statues; and less commonplace objects such as letters to the dead, weights, boundary stelae and a coffin inscribed with a ‘star clock’. With 3000 years of written culture to cover, this section was always going to be less focussed than the chronological narrative of decipherment. Nevertheless, it affords a good overview of ancient Egyptian writing. It struck me while writing that this overview section also offers a reasonably comprehensive introduction to Egyptian culture as we understand it today. The Hieroglyphs exhibition contains examples of most of the key types of Egyptian objects that we find in museums around the world. This is a testament to the comprehensive nature of the exhibition, but also to the heavy bias towards written (mostly elite) material in our understanding of ancient Egypt.

Egyptians in the narrative

In addition to telling a more nuanced narrative about the complex process and multiple individuals involved in decipherment, the exhibition clearly aims to include Egyptians, both past and present in the narrative. The chronological part of the exhibition begins with Arabic scholarly interest and breakthroughs in the decipherment of Hieroglyphs and ends with Egyptian Egyptologist Ahmed Kamal Pasha who began a hieroglyphic-Arabic dictionary that is now in the Biblioteca Alexandrina. The section on the Rosetta Stone includes considerable detail about the modern city of Rashid and a video of its most significant monuments today. I also enjoyed the comments from modern Egyptians ranging from highly respected scholars to schoolchildren, giving opinions on topics from the similarity of a funerary cone to a cookie (10 year old Fatima) to the admiration of (Egypt’s early 19th-century ruler) Muhammed Ali for Champollion (Dr Hend Mohamed Abdel Rahman of Minya University). I can see how the use of these comments could be interpreted as tokenistic, but they do help to draw together the chronological narrative of decipherment and the subsequent section on Egyptian written culture. Together with discussion of the multiple predecessors and collaborators of Champollion, the inclusion of medieval Arabic scholarship, 19th-century Egyptian Egyptologists and modern Egyptian voices, is an effort to avoid a narrative of decipherment as the product of a lone, white, male, genius. Whether or not it is enough to change the narrative in the mind of the visitor is not for me to say.

Crowd-pleaser

In many respects, this is a crowd-pleasing exhibition with many complimentary reviews. A clear narrative of decipherment is followed by a comprehensive review of Egyptian written culture, including various important objects, many of which are not regularly on display. The inclusion of aesthetically appealing or culturally important examples of the ‘usual suspects’ (objects commonly associated with ancient Egypt and displayed in museums) together with historically important and/or rarely seen artefacts makes for an exciting exhibition whether you are a professional Egyptologist or completely new to the subject. When I visited several people expressed disappointment that the exhibition did not include greater detail about how Hieroglyphs function as a writing system. If I have a criticism it is that there was a missed opportunity to prime the visitor with basic information about the Hieroglyphic writing system in the very first space. This might provide visitors with a better appreciation of some of the ideas, insights and dead-ends of the decipherment process and enable them to better appreciate the objects in the last section. The Abydos King List could have provided a follow-up to this process, breaking down the reading of common cartouches just as the Papyrus of Nedjmet breaks down the common components of the Book of the Dead. Nevertheless, the exhibition provides an excellent overview of the beginnings of Egyptology, from Greco-Roman and Arab scholars to the decipherment of Hieroglyphs and Ahmed Kamal Pasha’s dictionary. It also offers a superb overview of Egyptian written culture, with many showstoppers that anyone can appreciate. Inevitably the exhibition sidesteps the elephant-in-the-room of the status of the Rosetta Stone and calls for its repatriation, but it does present a complex nuanced view of decipherment and includes Egyptian voices and the Egyptian and Arabic scholars’ role in the decipherment process. If you’re in London this Christmas, take the opportunity to visit and experience it for yourself.

Find out more

Related posts

-

Exhibition Review: ‘Golden Mummies of Egypt’ at Manchester Museum

-

Exhibition Review: ‘Tutankhamun the Boy: Growing up in ancient Egypt’ at the Petrie Museum of Egyptian and Sudanese Archaeology

-

Review of the British Museum’s ‘Hieroglyphs: unlocking ancient Egypt’ exhibition