The Beecroft Art Gallery in Southend-on-sea, is currently showing an exhibition of paintings by local artist and archaeological illustrator, Alan Sorrell. Alan Sorrell featured in my earlier blog post and a small selection of his paintings were included in Southend Museum’s Wunderkammer exhibition, which I reviewed separately here. The new Beecroft Art Gallery exhibition is a much more extensive review of Sorrell’s Nubian paintings, created in southern Egypt and north Sudan in 1962 when he was commissioned by the Illustrated London News to record the UNESCO International Campaign to Save the Monuments of Nubia, in advance of the flooding of Lake Nasser behind the recently constructed Aswan High Dam. As a result the paintings in this exhibition reveal a long-vanished past. Although many of the temples were moved and can be visited in locations similar to their original position, their environment has inevitably changed.

I visited the exhibition in June 2025 and its a fantastic exhibition of paintings that are rarely seen, but represent an important aspect of the history of archaeology. If you want to visit, the Beecroft Art Gallery is on Victoria Avenue, a short walk from Southend Victoria station (Liverpool Street Line) and a slightly longer walk from Southend Central station (Fenchurch Street line).

The monuments of Nubia

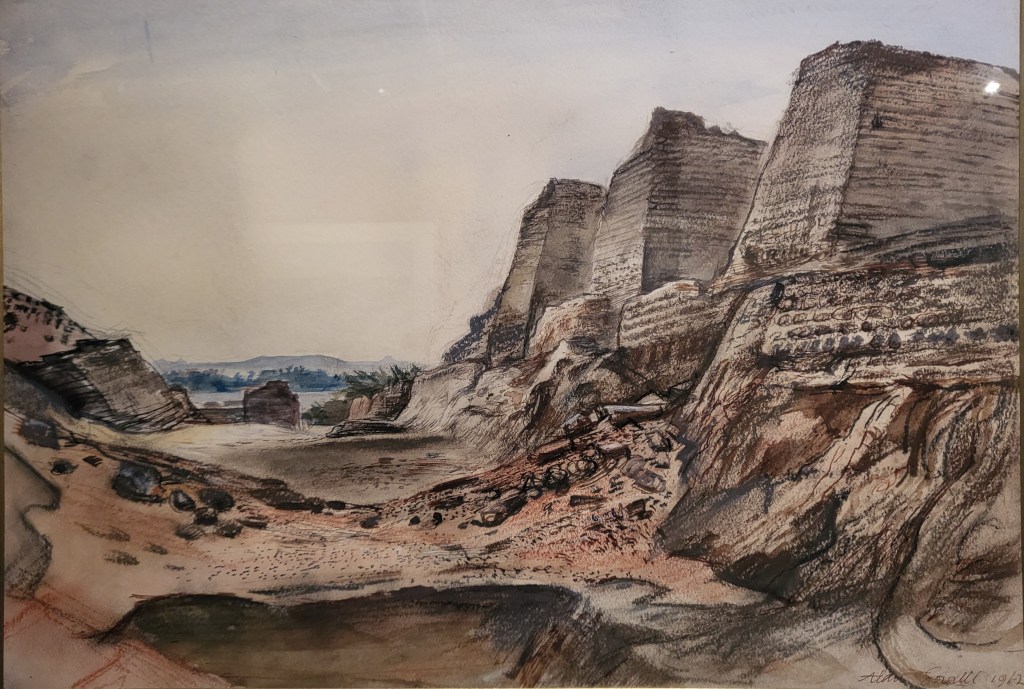

The exhibition begins with an introduction to Alan Sorrell and the UNESCO campaign, accompanied by a map made by Sorrell, showing the sites along the Nile from Thebes (Luxor) down to Semna in north Sudan. Each site name accompanied by a small sketch and numbers indicating which paintings came from there. The exhibition is organised as a down the Nile from south to north, beginning with an interesting painting identified as the temple of Hatshepsut from Semna West. I included the famous sketch of the outer defences of Buhen in my previous post about Alan Sorrell and his work, but this exhibition features another fantastic sketch of the walls of Buhen, this time from the external ditch (image below). Even in its damaged state, after over 3000 years of history, I would not like to mount an assault upon those walls!

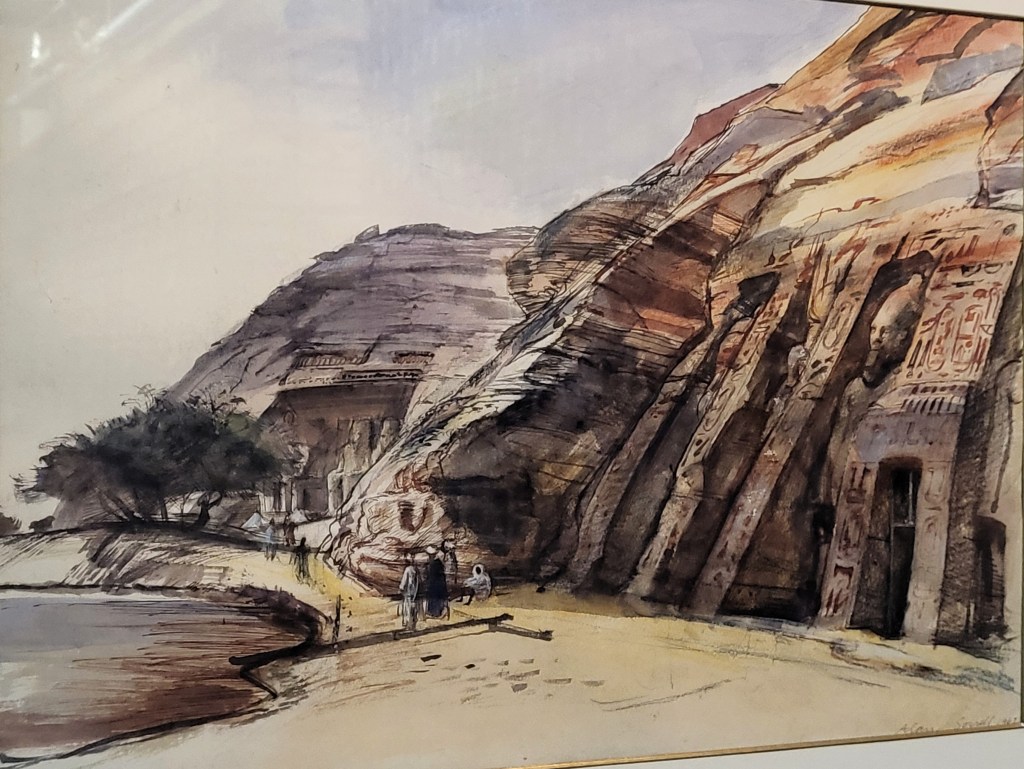

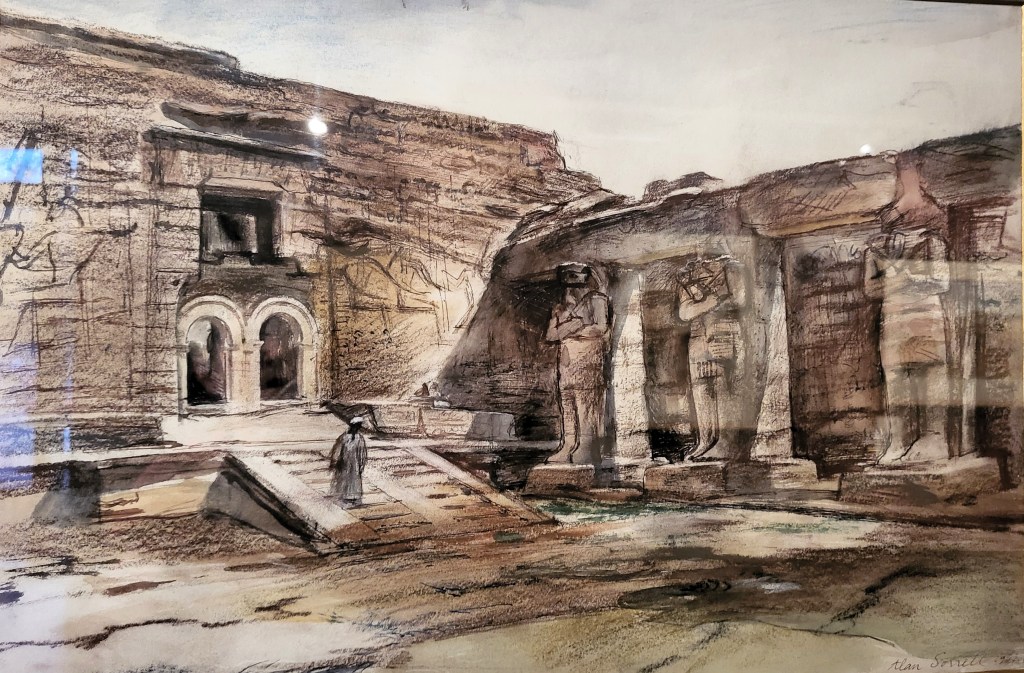

The roll of famous sites continues with a series of watercolours of Abu Simbel, poster-child for the UNESCO campaign (top image). There are some fantastic paintings of the interior, and a matched pair of paintings of Abu Simbel in the daytime and Abu Simbel at night. There are two particularly fine images showing water lapping against the entrance of Derr temple and the Wadi es-Sebua temple pylon, so different from the relocated temples high above the lake. Wadi es-Sebua also represents the multi-layered history of the region, with a painting of the temple interior showing the Ramesside court and pylon, with its central door divided in two by a later arch dating from Christian usage as a church (image below). Tumas and Sabagura forts, Ikhmindi Byzantine town, Amada, Gerf Hussein, Beit el-Wali and Kalabsha temples all feature in a roll-call of Nubian sites as you have never seen them before, or are likely to again. Kalabsha is particularly interesting, since Sorrell obviously visited once the temple had been deconstructed, and he painted the temple blocks at New Kalabasha ready for reassembly.

Lost landscapes

The exhibition includes various landscape paintings, including village scenes, Islamic tombs at Gebel Adda and a fascinating view of the ‘Belly of Stones’ at the second cataract (image below). The landscape images are incredibly interesting and increasingly important, given the huge changes in the landscape since Lake Nasser filled up. I am far too young to have seen an Egyptian inundation, or the Nubian landscape before Lake Nasser, but Sorrell’s painting of the ‘Belly of Stones’ emphatically demonstrates how it acquired its name. Although we should not fall for the idea that Egypt has never changed, it is nevertheless true that Sorrell’s paintings of the landscape and the archaeology within it reflect a world that would be immediately recognisble to someone from the 19th century, and in some cases perhaps to an ancient Egyptian, but is unfamiliar to us today.

The painting of the fort of Qustul (image below) was also interesting to me, because it reveals what the surviving remains at Qasr Ibrim might have looked like, when viewed from the desert, before Lake Nasser. Today Qasr Ibrim sits on a small island, its lower levels submerged by the lake, but before the lake it stood on a high bluff, overlooking the deep Nile valley, with the easiest approach from the desert. The information boards explicitly compare Sabagura, in painting 44, with Qasr Ibrim. The ruined buildings of Sabagura undoubtedly looked similar to the structures at Qasr Ibrim, but it was the position of Qustul fort in the landscape which I found so striking.

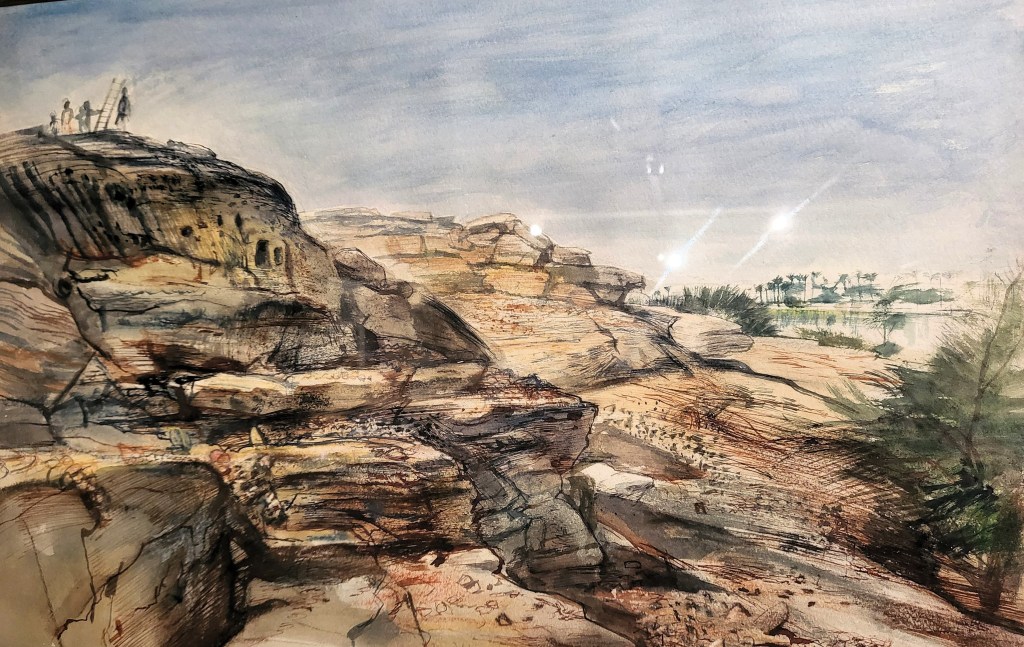

I found the painting of Toshka East (image below) particularly appealing. This is primarily a landscape painting, but in the centre left of the image halfway up the cliff are some interesting cuttings in the rock. It is difficult to assess their scale in a painting. The larger one almost certainly is a tomb entrance, while the smaller openings are either smaller tombs or niches for stelae, statues or other archaeological features. I have seen many similar examples all the way up the Nile valley, where local dignitaries created visible sepulchres in the cliffs close to their home city. The presence of the tombs also suggest the purpose of the small group of people on top of the cliff, presumably an archaeological party arriving with their ladder to access and record the features.

Village life

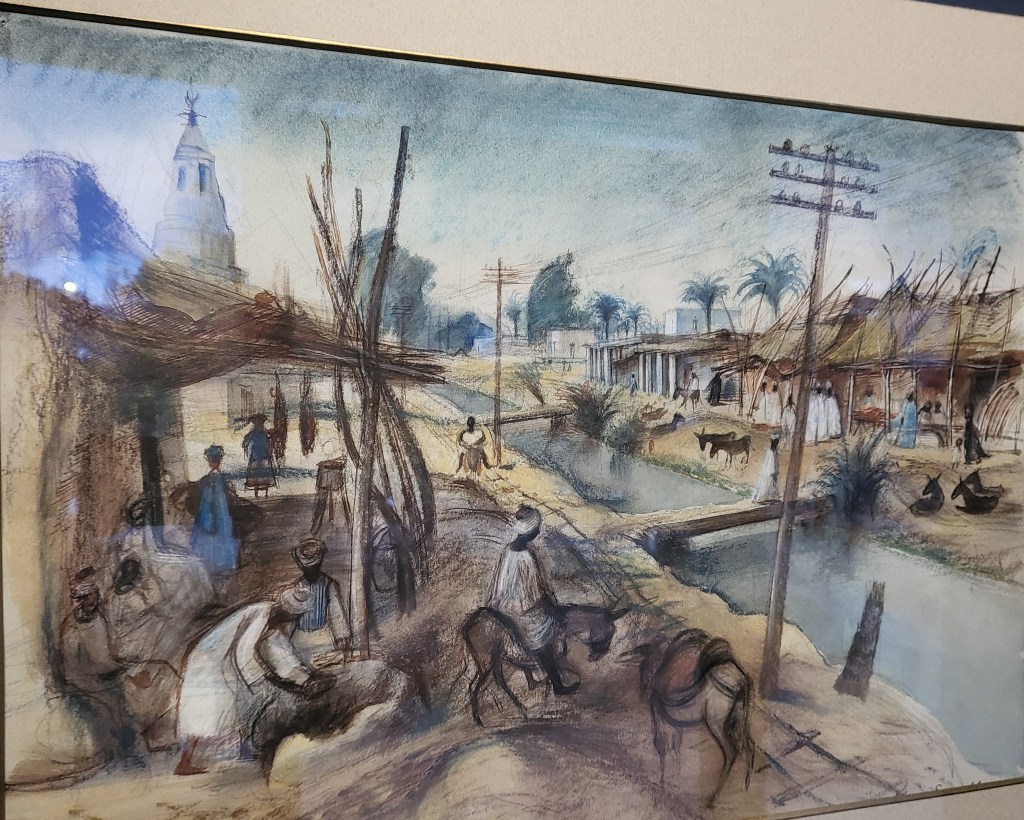

The several paintings of local Nubian villages are also interesting, both as a snapshot of Nubian culture at the time of the UNESCO campaign and also for Sorrell’s own views. The painting of villages like Ballana (image below), perhaps best known to archaeologists for its famous cemeteries, are emphatically about the real, lived-life of Nubians rather than the archaeology. This is consistent with Sorrell’s reported anger that in the drive to record the dead, the living Nubians had been largely forgotten (Sorrell and Sorrell 2018, 179). The information board points out that in many paintings from the 19th century onward, scenes such as these exhibited distinctive orientalist features that were both fanciful and inaccurate. Sorrell’s paintings might be considered orientalist in the sense that they were paintings of north African villages made by a western man, but there is no particular evidence of fanciful, inaccurate or anachronistic figures. While clothes obviously vary by class, wealth and sub-culture, many Egyptians, Nubians and Sudanese dress in a similar style to the people in Sorrell’s paintings.

Some minor criticisms

The exhibition was is well designed and laid out. The amount of archaeological detail that has been researched and incorporated into the information panels is impressive, but there are a few oddities in terms of the archaeological information. Curiously, the information panel for Buhen provides some fascinating detail about the, generally less well-known, Old Kingdom occupation at the site, but doesn’t mention the much more commonly discussed New Kingdom material. There is also a curious typo where the heading for a painting of the hypostyle hall of the Great Temple at Abu Simbel (number 06) reads ‘Queen’s Temple Interior, Abu Simbel’ when the blurb below correctly describes the image as the Hypostyle Hall of the Great Temple. The interior of the Temple of Hathor/Nefertari is painting number 07, which is correctly described. Given that I believe the curator is an art curator, rather than an archaeologist, I am quite impressed at the level of accurate archaeological detail.

Illustrator of Archaeologists

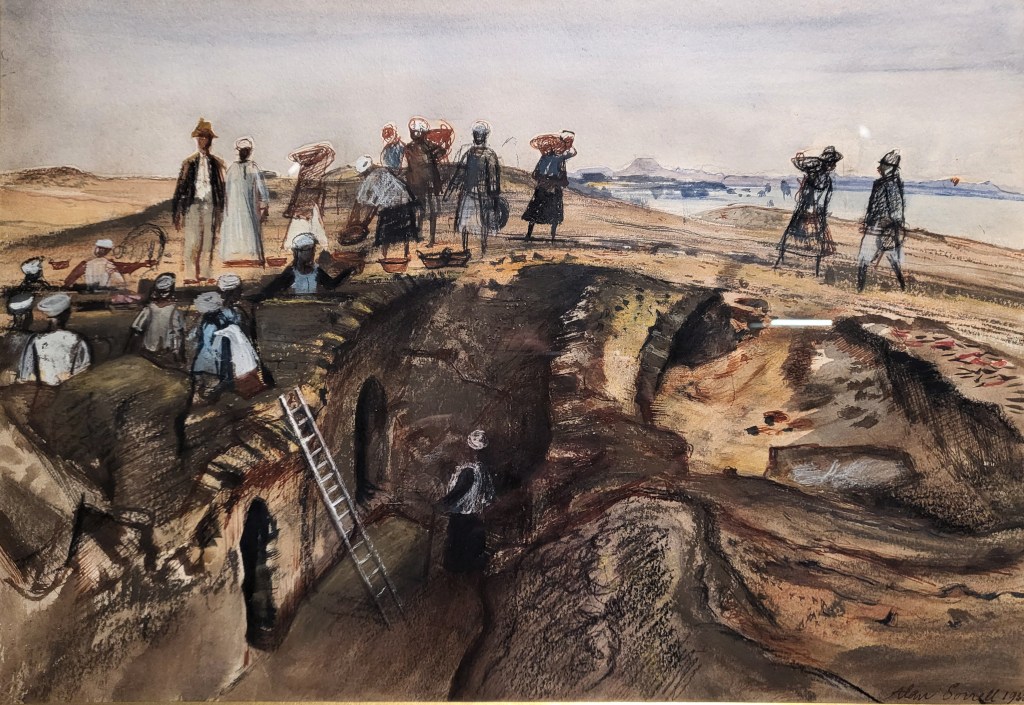

Sorrell, did not just paint landscapes, villages and archaeology, he also painted the archaeologists. One section of the exhibition included three of Sorrell’s paintings of archaeological excavations in progress. I commented on one of archaeologists drilling in the Great Temple at Abu Simbel in a previous post. The other two, of excavations at Arminna are wholly new to me, and fascinating for it. They show a large number of people in long Egyptian or Nubian robes with turbans, around large open excavations, with visible upstanding archaeology. One painting shows a couple of folk in European dress, but who they are is uncertain. The others are presumably locally hired workers and Qufti archaeologists. These images are interesting because theexcavations follow the tradition of the late 19th and early 20th century with big, open excavations and large numbers of workers supervised by relatively few trained archaeologists. In subsequent decades archaeology moved towards smaller excavations with more limited, more highly trained archaeological staff. At the same time, archaeological methods were developing towards more refined stratigraphic analysis and increasingly scientific processes, some of which would be applied to the data from the Nubian Rescue Campaign. These paintings therefore stand at a threshold in archaeological practice, towards the end of 19th century practices and the beginning of archaeological methods recognisable on sites today.

References

Julia Sorrell and Mark Sorrell, 2018. Alan Sorrell: The Man Who Created Roman Britain, Oxbow.

All photographs are the Author’s own, taken in June 2025 at the Alan Sorrell: Nubia exhibition at the Beecroft Art Gallery Southend.