NOTE: Inevitably as this post discusses mummified people it includes images of them and references to them that some may find offensive.

In my previous post I reviewed Manchester Museum’s recent Golden Mummies exhibition. Although this exhibition has been touring for several years and in development for even longer, its return to the UK in early 2023 was highly topical. In January (presumably on a slow news day) the Daily Mail trumpeted that ‘woke museum chiefs’ have stopped using the word ‘mummy’ and instead refer to ‘mummified people’ or ‘mummified remains’. Subsequent fact-checking by Reuters demonstrated that this was something of an exaggeration, undoubtedly to bolster the ‘culture wars’ theme underlying so many of the Mail’s more huffy stories. Nevertheless, it does reflect changing attitudes toward mummified people and discussions about the propriety of displaying human remains in general. This discussion has been reflected in books like Christina Riggs’ Unwrapping Ancient Egypt, the British Museum’s Regarding the Dead, and Angela Stienne’s Mummified. It also forms part of general discussions and exhibitions on the subject of colonialism in Egyptology and museums in general.

Manchester Museum has long been associated with research into mummified ancient Egyptians, from Margaret Murray‘s scientific unwrapping of Khnum-Nakht at Manchester in 1908, to the Manchester Mummy Project of the late 20th century. Although ground-breaking in its day, much of this research was preoccupied with bio-anthropological and palaeo-pathological matters. It was also subject to the prejudices and biases of those specific periods, ranging from scientific racism to voyeurism and simple disregard for the humanity of the subjects, which have been thoroughly considered in books like Unwrapping Ancient Egypt and Mummified.

The Golden Mummies exhibition largely eschews this history of scientism (although early formats and one chapter of the catalogue include bio-anthropological details) and focuses on mummified ancient Egyptians as the ancient Egyptians saw them. In this, the Golden Mummies exhibition offers a new perspective on the question of how they should be understood and discussed in our culture.

‘Mummies’

As many schoolchildren know, ‘mummy‘ comes from the black, bitumen-like resin that is often found coating mummified ancient Egyptians. The word derives from the Persian for ‘asphalt’, entering European languages via the Arabic ‘mumiya‘ (bitumen/ mummified person) and Latin ‘Mumia‘. Given its long usage for embalmed and preserved ancient Egyptians, ‘mummy’ is inevitably associated with the period of European imperialism and colonialism that accompanied the earliest archaeological (and rather less than archaeological) research in Egypt. It is also strongly associated with the pop-culture voyeurism of mummy unrollings, and appropriation of ‘the mummy’ into gothic horror, which flourished as part of the Egyptomania of the 19th and 20th centuries. It is because of this history, and the objectification of human remains as something ‘less than human’, that other terms have been suggested as more appropriate.

‘Mummified remains’

Of all the possible alternatives to ‘mummy’, I think ‘mummified remains’ is the worst. If ‘mummy’ is dehumanising, how much more so is reducing a person to mere ‘remains’? To me, it implies both incompleteness in the corpse and some level of decomposition. Double yuck! I’m not someone who likes human remains at the best of times so associating a complete mummified person with decomposing bits feels deeply gross. To my mind ‘mummified remains’ is a term only fit to be used for animal mummies or mummified body parts, separate from the rest of the body.

‘Mummified people’

‘Mummified people’ appears to be preferred by many, and it’s easy to see why. It clearly relates the new term to the well-known and understood concept of ‘mummification’, it brings a sense of wholeness and completeness (although this belies the unfortunate state of some mummified people), and it emphasises the humanity of the subject. These are people, not things!

Unfortunately, ‘mummified people’ is not without problems. It is fundamentally a modern western term, rooted in our interests in individuality, bodily identity, and the humanity of the dead. None of these are intrinsically bad, but it’s worth questioning if we should be replacing ‘mummy’ with yet another western term applied to an ancient culture, located in a formerly colonised country. Calling them ‘mummified people’ cossets our anxieties about how mummified ancient Egyptians are treated, while still centering our attitudes to the body and the dead.

Furthermore, talking about ‘mummified people’ is little more than ‘window-dressing’ if, as archaeologists and Egyptologists, we continue to perpetuate voyeuristic and orientalist attitudes toward them in our dealings with the public. Unless we act on changing attitudes and convey them in our museum labels, catalogues, blogs, twitter, and public descriptions, museum professionals talking about ‘mummified people’ is the ultimate in superficiality.

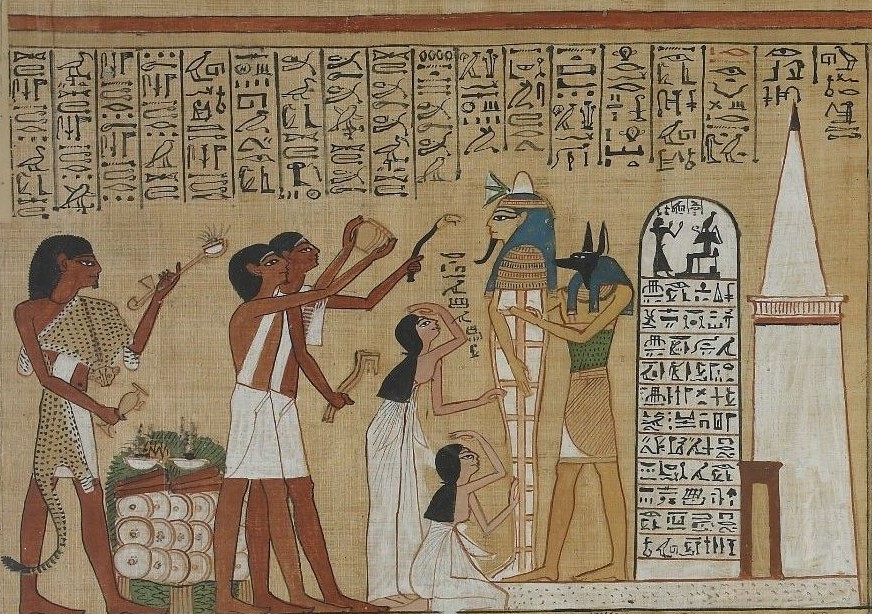

As the Golden Mummies exhibition reminded me, to the ancient Egyptians, the mummified aren’t just ‘mummified people’, they are much, much more than mere ‘people’ who have been embalmed. A mummified ancient Egyptian, comprising embalmed corpse and wrappings, plus mask, foot covering, cartonnage, and coffins where present, was described as a sah (plural sahw) in the ancient Egyptian language. Complete, beautifully decorated, and often gilded, sahw were suitable receptacles for the semi-divine spirit of their ancient Egyptian owner, functioning much like a cult statue for a god. Sahw are not just the preserved remains of individual humans as ‘mummified people’ implies, they are cult statues for semi-divine spirits that transcend the physical and are more than human. Calling them ‘mummified people’ diminishes them, rendering sahw less than they were originally conceived to be.

Sahw

The obvious solution is to call mummified ancient Egyptians ‘sahw’ as the ancient Egyptians did, centering the ancient Egyptian concept and understanding. Some may object that ‘sahw’ is not widely known or understood. This is true, but changing from ‘mummy’ to ‘mummified person’ also requires explanation. Instead of settling for a term that cossets our anxieties about human remains, centres our view of humanity, and is likely to be derided as ‘woke’ window dressing, we should be using the opportunity to promulgate the ancient Egyptian word, and the concepts behind it. Press publicity for Golden Mummies expressed surprise that mummification was about more than merely preserving the body. Using an ancient Egyptian term for the mummified gives us an opportunity to explain the processes and purposes of mummification in ancient Egypt, and counter superficial, pop-culture understandings more efficiently. It should also help to prevent hijacking by those more interested in centering an ‘anti- anti- colonialism‘ (as Dan Hicks calls it), ‘culture wars’ agenda. Changing our terminology for mummified ancient Egyptians should centre them and their understanding, not our preoccupations.

References

For the ancient Egyptian word ‘sah‘ see “sꜥḥ” (Lemma ID 129130) https://thesaurus-linguae-aegyptiae.de/lemma/129130, edited by Altägyptisches Wörterbuch, with contributions by Lisa Seelau, in: Thesaurus Linguae Aegyptiae, Corpus issue 17, Web app version 2.01, 12/15/2022, ed. by Tonio Sebastian Richter & Daniel A. Werning by order of the Berlin-Brandenburgische Akademie der Wissenschaften and Hans-Werner Fischer-Elfert & Peter Dils by order of the Sächsische Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Leipzig (accessed: 4/24/2023)

For more on the treatment of mummified ancient Egyptians see;

- Fletcher, Alexandra; Antoine, Daniel; Hill, J.D. (eds.), 2014. Regarding the Dead: Human Remains in the British Museum. London: British Museum Press.

- Riggs, Christina, 2014. Unwrapping Ancient Egypt. London: Bloomsbury

- Stienne, Angela, 2022. Mummified: The stories behind ancient Egyptian mummies in museums. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

For more on racism in early 20th-century Egyptology see;

- Sheppard, Kathleen, 2011. Flinders Petrie and Eugenics at UCL. Bulletin of the History of Archaeology 20(1): 16-29. DOI: 10.5334/bha.20103;

- Challis, Debbie, 2013. The Archaeology of Race: The Eugenic Ideas of Francis Galton and Flinders Petrie. New York/London: Bloomsbury Academic.

The Golden Mummies exhibition catalogue contains a much fuller treatment of the exhibition themes, including the role of mummification in divinisation and the colonial context for the collection; Price, Campbell, 2020. Golden Mummies of Egypt: Interpreting Identities from the Graeco-Roman Period. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Find out more

Related posts

-

Two 19th centruy paintings of the Colossi of Memnon

-

“How do you solve a problem like Marea?” Locating a site from the exhibition, ‘Alan Sorrell ‘Nubia”.

-

Exhibition Review: Alan Sorrell ‘Nubia’

Pingback: Review of the re-displayed Egypt and Sudan gallery of the Manchester Museum – Scribe in the House of Life: Hannah Pethen Ph.D.

Pingback: Review of the re-displayed Egypt and Sudan gallery of the Manchester Museum – Scribe in the House of Life: Hannah Pethen Ph.D. - NACION ASTRAL